The daily writing routines of Joan Didion, Susan Sontag, Haruki Murakami and other famous writers

“After 8:00 p.m. I tend to be very stupid and we won’t talk about this.”

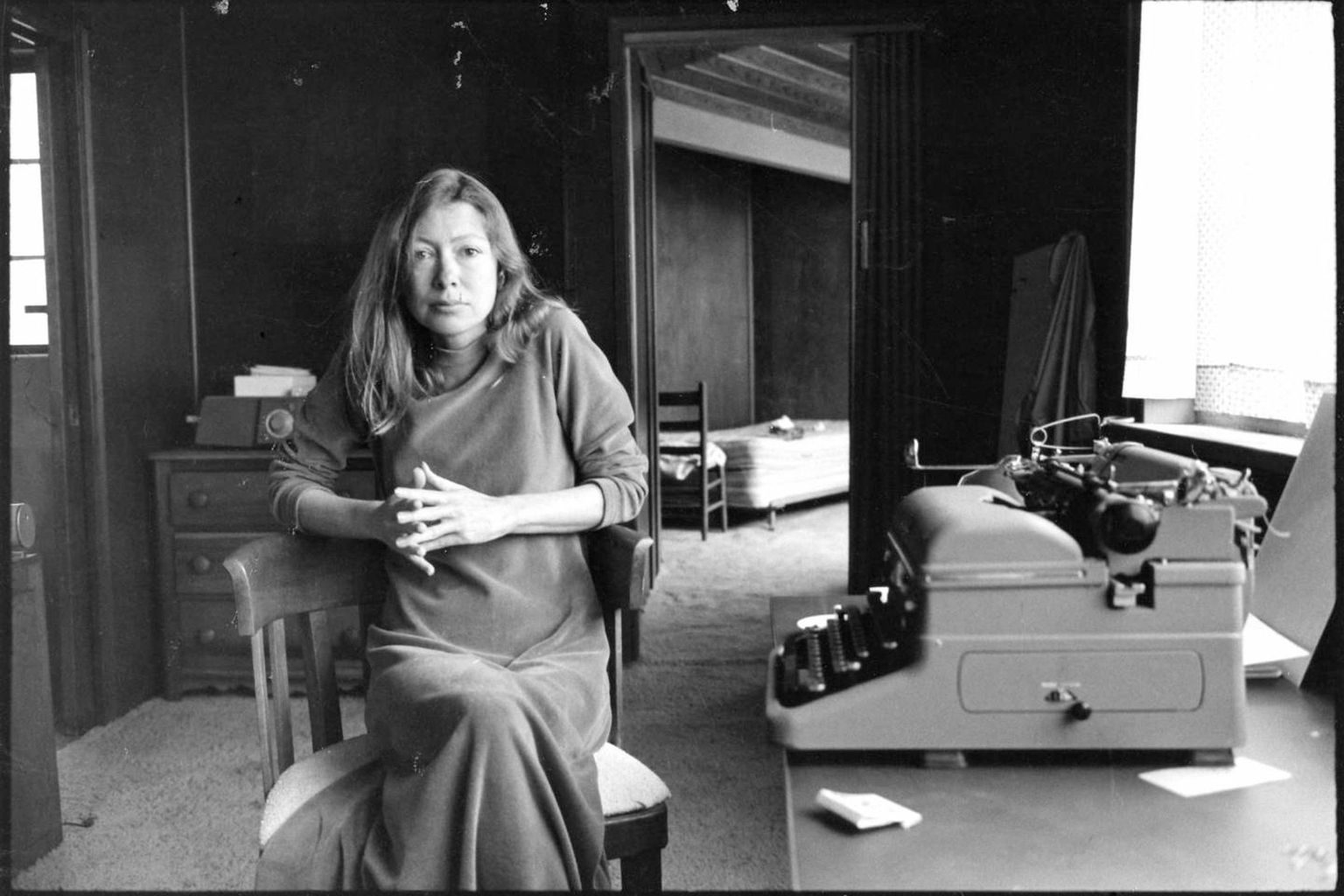

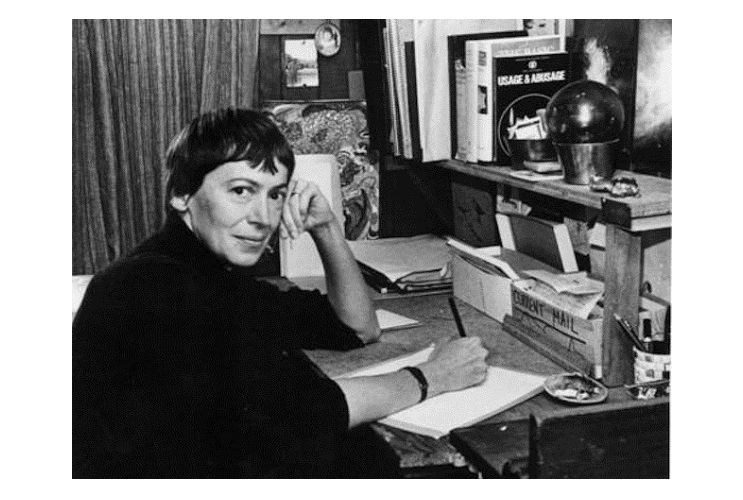

Joan Didion in her home in California, 31 March, 1972. Photo by Jill Krementz.

The internet is full of sites claiming to hold the keys to literary success. ‘Write a Book in 10 Simple Steps’ offers one page selected more or less at random from 131,000,000 search results, while countless others offer to impart the wisdom to ‘Make You a Better Writer with One Simple Trick’, if only you’d click that SEO-addled link. They’re all enticing offers—who wouldn’t want to write a novel in 30 days?—though rarely worth the server space hosting them. That’s because there’s only one trick guaranteed to turn your blank Google Doc into the literary opus of your dreams, and that's to stop looking for writing tricks and simply sit down and write.

Sad as it may be, no moonlight ritual will let the words flow through you like water from a tap, and no incantation will turn those words into the kinds of elegant prose your favourite writers seem to churn out with ease. Writing is hard, there are no shortcuts, and—to this writer’s eternal despair—the only way to do it is to get on with the hard, shortcut-less work of doing it.

Of course, knowing there are no shortcuts won’t necessarily stop you from seeking them. Case in point: I simply cannot resist the urge to scrutinise the daily routines of successful writers. If you’ve ever done this—and the preponderance of websites chronicling such things indicates you might—you’ll understand the banal satisfaction of learning how your idols divided up the hours of their days. Hunter S. Thompson rose at three p.m. to a breakfast of Chivas Regal and cigarettes? This is the stuff I get out of bed at eight a.m. to boot up my ageing MacBook for.

Occasionally I tell myself that I read such daily routines for fun, a little procrastinatory distraction between editing work. But more often than not a part of me is convinced I’m actually doing so in the name of self-improvement. In this fantasy, I’m not wasting precious time on the internet by finding out that Joan Didion spent most of her day “just sitting there, trying to form a coherent idea”; I am gleaning advice about the most writerly way to schedule my day.

Read enough of these routines and it can start to seem that the reason Haruki Murakami was able to write Norwegian Wood was that he got up at four a.m., wrote for six hours and then went for a 10-kilometre run—the obvious implication being that if you also got up at four a.m., wrote for six hours and then went for a 10-kilometre run you could also bang out a New York Times best-seller every couple of years.

But then the contradictions arise. I know that Didion started writing at about five in the afternoon, and was lucky to get a paragraph down before retiring for the evening, never so much as setting foot in a running shoe. So should I rise at four a.m. or three p.m.? Live the life of a Renaissance man or an internet-addled slob? Take five years to work on a manuscript or one? Write drunk or sober? The variables are near-endless, as are the questions that may invariably flood your mind about what it is, exactly, you are doing with your life.

Of course, deep down we understand that the relationship between ordering your life a certain way and producing works of heartbreaking genius is largely arbitrary. The variables are surely correlative, not causative, and examining them in any serious way makes about as much sense as inspecting the entrails of a sacrificed chicken. Still, there’s something about laying the creative process out like a train timetable that I can’t quite shake. With that enjoyment in mind—and provided we approach the following as a curio rather than a lesson—I see no reason we can’t also peer a little into the daily lives of famous writers, just for the hell of it. So long as we all get back to work in an hour or so.

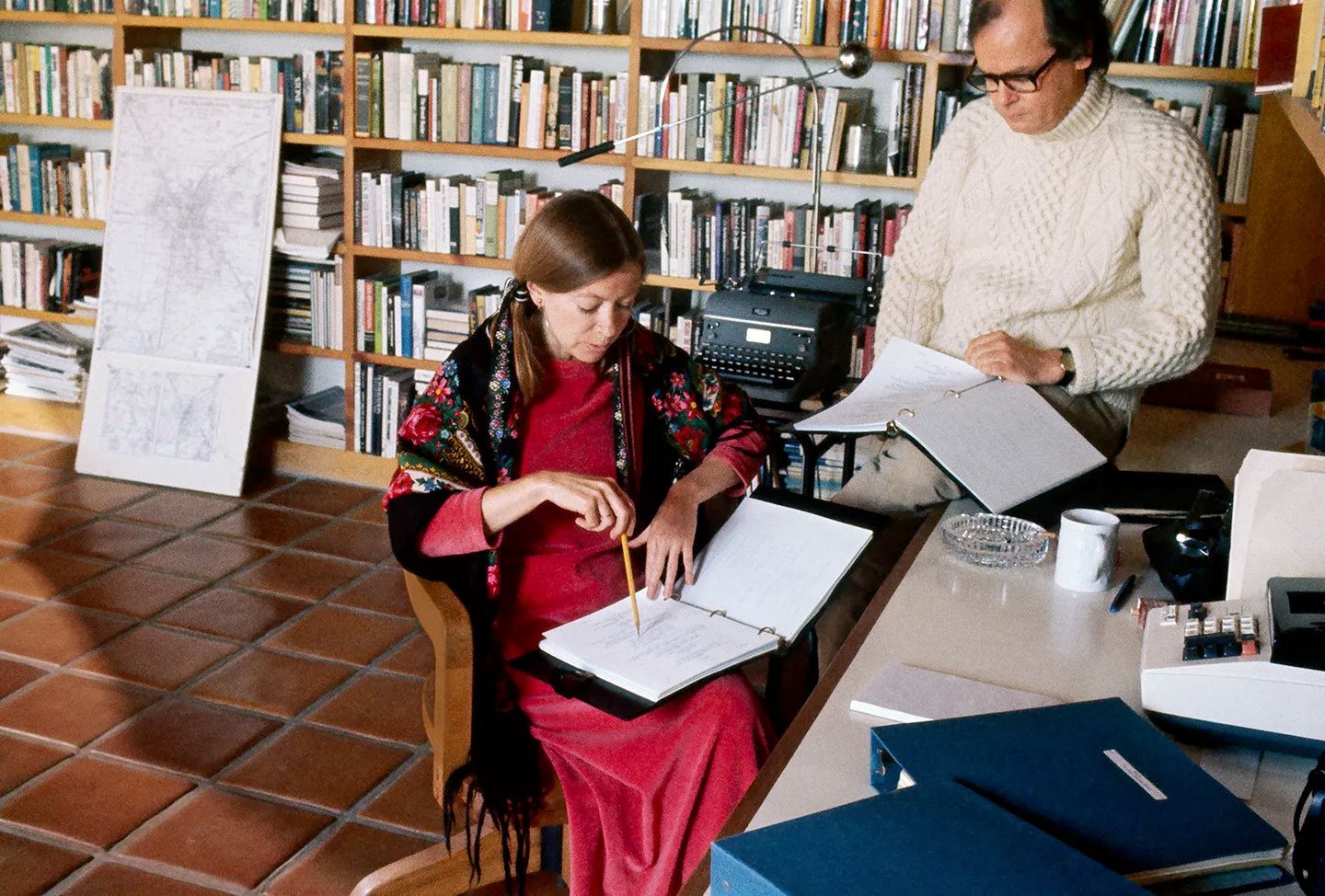

Didion and her husband/collaborator John Gregory Dunne, 1972. Photo: Henry Clarke

Joan Didion

Didion outlined her writing routine in this 1968 interview with The Paris Review. And while I could paraphrase it for you, due reverence dictates I let The White Album author speak for herself:

“I need an hour alone before dinner, with a drink, to go over what I’ve done that day. I can’t do it late in the afternoon because I’m too close to it. Also, the drink helps. It removes me from the pages. So I spend this hour taking things out and putting other things in. Then I start the next day by redoing all of what I did the day before, following these evening notes. When I’m really working I don’t like to go out or have anybody to dinner, because then I lose the hour. If I don’t have the hour, and start the next day with just some bad pages and nowhere to go, I’m in low spirits. Another thing I need to do, when I’m near the end of the book, is sleep in the same room with it. That’s one reason I go home to Sacramento to finish things. Somehow the book doesn’t leave you when you’re asleep right next to it. In Sacramento nobody cares if I appear or not. I can just get up and start typing.”

In 2005, some 37 years later, Didion told another reporter that she usually spends “most of the day working on a piece not actually putting anything on paper, just sitting there, trying to form a coherent idea and then maybe something will come to me about five in the afternoon and then I’ll work for a couple of hours and get three or four sentences, maybe a paragraph.” Hard same.

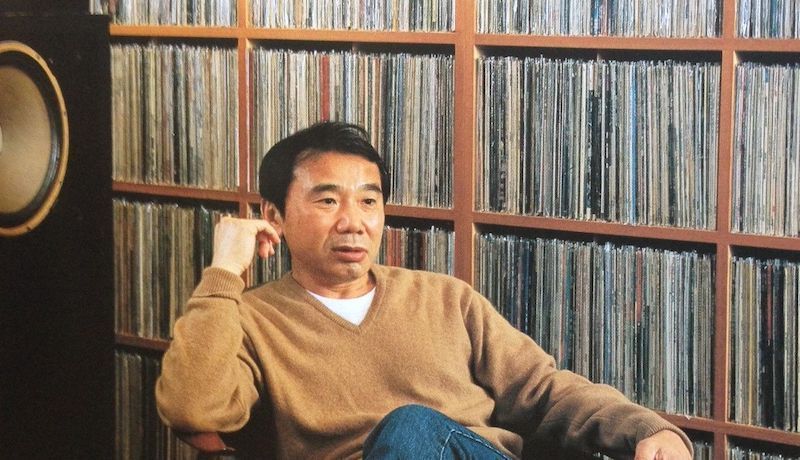

Haruki Murakami

If you know anything about the extracurricular activities of Haruki Murakami, you probably know he enjoys running (and music). But to hear the Wind-Up Bird Chronicle author explain it, as he did in 2004, running and writing aren’t entirely unconnected pursuits:

“When I’m in writing mode for a novel, I get up at four a.m. and work for five to six hours. In the afternoon, I run for ten kilometers or swim for fifteen hundred meters (or do both), then I read a bit and listen to some music. I go to bed at nine p.m.

“I keep to this routine every day without variation. The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind.

“But to hold to such repetition for so long—six months to a year—requires a good amount of mental and physical strength. In that sense, writing a long novel is like survival training. Physical strength is as necessary as artistic sensitivity.”

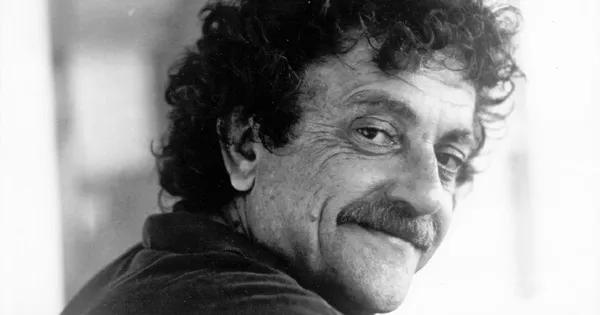

Kurt Vonnegut

Two decades after he’d given up on his youthful dreams of becoming an anthropologist, and four years before he penned Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut, who was teaching at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, wrote to his wife about his daily routine. It involved “several belts” of Scotch and a lot of sit-ups:

“I awake at 5:30, work until 8:00, eat breakfast at home, work until 10:00, walk a few blocks into town, do errands, go to the nearby municipal swimming pool, which I have all to myself, and swim for half an hour, return home at 11:45, read the mail, eat lunch at noon. In the afternoon I do schoolwork, either teach or prepare. When I get home from school at about 5:30, I numb my twanging intellect with several belts of Scotch and water ($5.00/fifth at the State Liquor store, the only liquor store in town. There are loads of bars, though.), cook supper, read and listen to jazz (lots of good music on the radio here), slip off to sleep at ten. I do pushups and sit ups all the time, and feel as though I am getting lean and sinewy, but maybe not.”

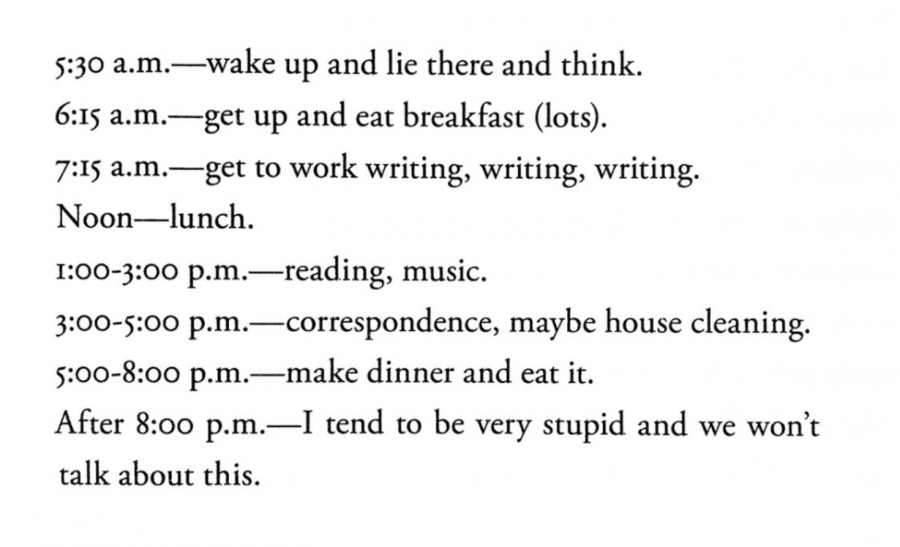

Ursula K. Le Guinn

The Left Hand of Darkness author had a strict schedule, starting at 5:30 a.m. and finishing somewhat vaguely at 8 p.m:

Beyond the self-self-deprecating humour, the most interesting thing to be gleaned from Le Guinn’s list is how much time a writer might reasonably be expected to actually sit down and write—about five hours in Le Guinn’s case, the remainder of her day taken up with pursuits like reading, music, “maybe house cleaning,” and then dinner. Others in this list wrote for even less time, a reminder that it’s quality, not quantity, that counts when you want to be a living legend.

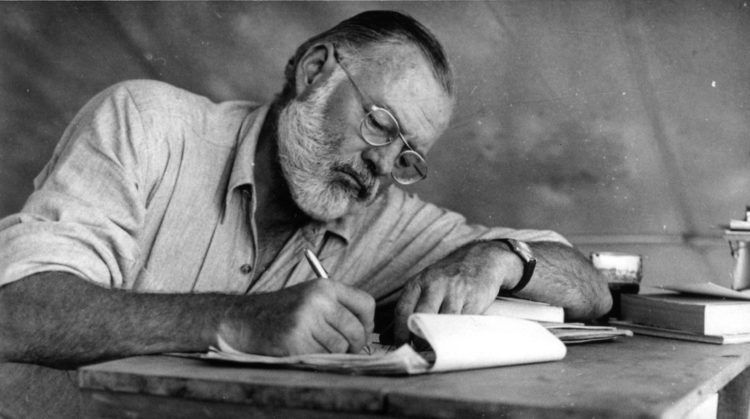

Ernest Hemingway

“When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning as soon after first light as possible,” the [insert incredibly well-known book of your choosing here] author told The Paris Review in 1958. “There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write.”

Irrespective of how late (and alcohol-soaked) the night before had been, he would rise at 5:30 a.m. and begin by reading the previous day’s efforts half an hour later. With the revisions done, he would then get to work writing the first draft of the next batch of words—between 500 to 1000 of them a day. “You have started at six in the morning, say, and may go on until noon or be through before that. When you stop you are as empty, and at the same time never empty but filling, as when you have made love to someone you love.” TMI, perhaps, but who are we to question the man for whom the bell tolls and sun rises?

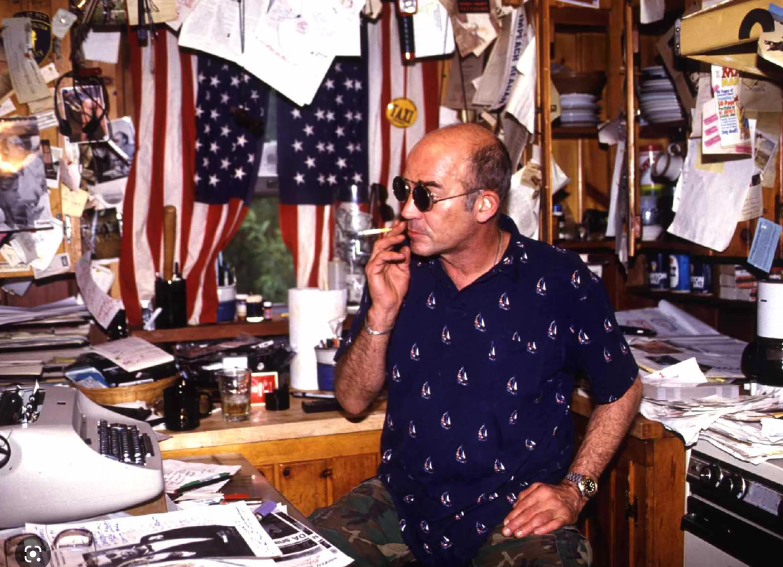

Hunter S. Thompson

I’m including Thompson’s supposed daily routine here because a) I mentioned it in the intro, b) it’s funny and c) because the 16-year-old version of me who I’m now embarrassed to admit desperately wanted to be like Hunter S. Thompson just really would have wanted me to.

3:00 p.m. rise

3:05 Chivas Regal with the morning papers, Dunhills

3:45 cocaine

3:50 another glass of Chivas, Dunhill

4:05 first cup of coffee, Dunhill

4:15 cocaine

4:16 orange juice, Dunhill

4:30 cocaine

4:54 cocaine

5:05 cocaine

5:11 coffee, Dunhills

5:30 more ice in the Chivas

5:45 cocaine, etc., etc.

6:00 grass to take the edge off the day

7:05 Woody Creek Tavern for lunch-Heineken, two margaritas, coleslaw, a taco salad, a double order of fried onion rings, carrot cake, ice cream, a bean fritter, Dunhills, another Heineken, cocaine, and for the ride home, a snow cone (a glass of shredded ice over which is poured three or four jiggers of Chivas)

9:00 starts snorting cocaine seriously

10:00 drops acid

11:00 Chartreuse, cocaine, grass

11:30 cocaine, etc, etc.

12:00 midnight Hunter S. Thompson is ready to write

12:05-6:00 a.m. Chartreuse, cocaine, grass, Chivas, coffee, Heineken, clove cigarettes, grapefruit, Dunhills, orange juice, gin, continuous pornographic movies.

6:00 the hot tub-champagne, Dove Bars, fettuccine Alfredo

8:00 Halcyon

8:20 sleep

And that is how you see Rolling Stone through its most creatively fertile period. Except, Thompson didn’t actually work like this. (Who could?) This routine has been re-published online so many times that it’s effectively become gospel. But as the literary journal Beatdom points out, not only is it not true, but it was never even intended to be taken seriously. The whole thing was created as a sort of literary project by the writer E. Jean Carroll (now also famous for her recent successful sexual assault lawsuit against Donald Trump), who published an unconventional biography of Thompson in 1993.

Carrol made the controversial decision to alternate between fiction and non-fiction throughout the book, and took the fictional route when it came to how he structured his time. But that hasn’t stopped plenty of otherwise reputable publications from reporting it as truth—see Mental Floss, the Independent, and Open Culture—a fact that would surely please Thompson if he were around today and capable of being pleased about anything.

William Gibson

Gibson, who in between more or less inventing cyberpunk also coined the term ‘cyberspace’, has a far more sensible (and factual) routine. As he told a reporter in 2011:

“When I’m writing a book I get up at seven. I check my e-mail and do Internet ablutions, as we do these days. I have a cup of coffee. Three days a week, I go to Pilates and am back by ten or eleven. Then I sit down and try to write. If absolutely nothing is happening, I’ll give myself permission to mow the lawn. But, generally, just sitting down and really trying is enough to get it started. I break for lunch, come back, and do it some more. And then, usually, a nap. Naps are essential to my process. Not dreams, but that state adjacent to sleep, the mind on waking…

“As I move through the book it becomes more demanding. At the beginning, I have a five-day workweek, and each day is roughly ten to five, with a break for lunch and a nap. At the very end, it’s a seven-day week, and it could be a twelve-hour day.

“Toward the end of a book, the state of composition feels like a complex, chemically altered state that will go away if I don’t continue to give it what it needs. What it needs is simply to write all the time. Downtime other than simply sleeping becomes problematic. I’m always glad to see the back of that.”

Susan Sontag

The essayist, novelist and philosopher was clearly in need of a circuit breaker in 1977, when she wrote the following in her (since published) diary:

- Starting tomorrow — if not today:

- I will get up every morning no later than eight. (Can break this rule once a week.)

- I will have lunch only with Roger [Straus]. (‘No, I don’t go out for lunch.’ Can break this rule once every two weeks.)

- I will write in the Notebook every day. (Model: Lichtenberg’s Waste Books.)

- I will tell people not to call in the morning, or not answer the phone.

- I will try to confine my reading to the evening. (I read too much — as an escape from writing.)

- I will answer letters once a week. (Friday? — I have to go to the hospital anyway.)

Eighteen years later, in—you guessed it—The Paris Review, she would follow this up with a more detailed overview of her routine:

“I write with a felt-tip pen, or sometimes a pencil, on yellow or white legal pads, that fetish of American writers. I like the slowness of writing by hand. Then I type it up and scrawl all over that. And keep on retyping it, each time making corrections both by hand and directly on the typewriter, until I don’t see how to make it any better… I write in spurts. I write when I have to because the pressure builds up and I feel enough confidence that something has matured in my head and I can write it down. But once something is really under way, I don’t want to do anything else. I don’t go out, much of the time I forget to eat, I sleep very little. It’s a very undisciplined way of working and makes me not very prolific. But I’m too interested in many other things.”

Looking for more words of wisdom? Try ‘Sixty-nine pages of writing advice from Werner Herzog, Flannery O’Connor and more or less every other artist who’s ever put pen to paper’