How Matt Rogers became the most successful writer you've never heard of

He spends just two hours a day writing, yet manages to publish a new novel every three months. Meet Matt Rogers, inventor of one of the most extreme writing methods we've ever encountered and the (possible) future of publishing.

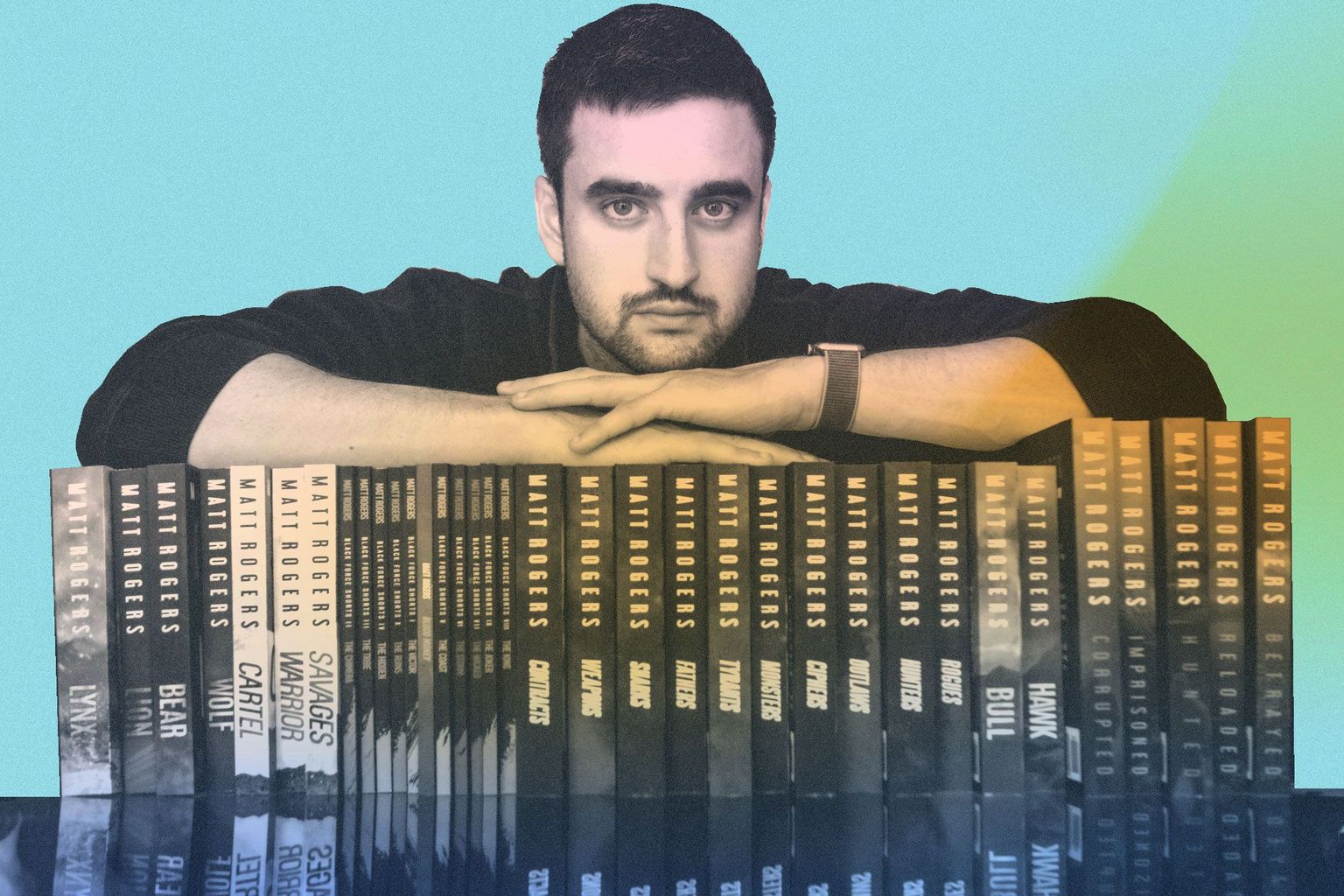

Photography: Craig Sillitoe Photo illustration: Emily Thiang

Every morning, Matt Rogers sets off on a 10-kilometre run from his apartment in Melbourne’s inner north. By the time he gets back home, at around 10 A.M., the endorphin high should have put him in the right headspace for writing.

Either way, endorphins or no, writing is what Rogers proceeds to do—at an eyelash-searing clip. Over the next couple of hours he’ll type somewhere between 1,500 and 2,000 words—what many writers might hope to churn out in a week. “It takes me less than two hours,” he says. “And I do that seven days a week. By this point, it's an automatic habit.”

This is how the 24-year-old composes the action thrillers that have made him one of Australia’s most successful authors: with industrial prolificacy. Since 2016, Rogers has released a new title every three months. He knows what his readers want—galloping plots, abundant action, a cast of enduring characters—and he’s mastered the art of giving it to them with remarkable consistency: 28 novels and 11 novella-length shorts, published in the space of five years, for which he pockets about $40,000 a month.

And all without the help of a publisher. Or, for that matter, a household name.

Rogers was 15 when he started work on his first full-length novel, a 100,000-word tome about a teenager recruited to hunt down mutants. Like any aspiring writer, he dreamed of a book deal, of hardback copies stacked on bookstore display tables. But some cursory research into the publishing industry provided a reality check. “I found all these agents and got a sense of how it worked,” he says. “And I realised how tough an industry publishing would be to break into. You can have an incredible book, and it can still be so hard to be noticed by anyone.”

It was a harsh realisation, one all would-be authors eventually come to terms with. Literary agents, tasked with selling an author's book proposal to a publishing house, can receive hundreds of manuscripts a week. Of the few they recommend to a publishing house, just a fraction will actually be bought. And only a fraction of those will ever find their way onto someone’s bedside table. Success hinges on connections and blind luck almost as much as talent; even if you have something the reading public is after, the odds of you getting it to them are slim.

Disheartened by the labyrinthine route to literary success, Rogers decided to pursue a less precarious line of work. He enrolled in law at Monash University after finishing high school. But less than a semester into his studies, he was overcome by the niggling feeling that he had been too quick to abandon his dreams. Despite the roadblocks thrown up by the profession’s gatekeepers, he paused his studies and resolved to give writing a proper chance. “I figured I'd go back to university after a year if I couldn't support myself with writing”, he says.

In the time it takes a publisher to print and distribute a single book, Rogers could have released four novels.

Under the cosh of his self-imposed deadline, Rogers applied himself with a sense of urgency. In just three months he turned out his first “real” novel, an action thriller in the Robert Ludlum tradition called Isolated. The book told the story of an ex-special forces agent named Jason King who took it on himself to track down the perpetrators of a murder in rural Australia.

Plenty of action thriller writers have found success with traditional publishers. But rather than roll the dice with a literary agent, Rogers decided to self-publish Isolated through Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP), Amazon’s self-publishing platform. He set the cost at 99 cents, the minimum allowed for a KDP book. “I left it as cheap as I could,” Rogers says. “I just needed people to see it.”

And see it they did. Isolated did well, and three months later Rogers released the first of what would become many sequels, Imprisoned. This time he priced it at $3.99. “That got even more sales—and that’s what allowed me to transition over and do it for a job.” He dropped out of law school, a safety net he no longer needed, and became the writer his teenage self had dreamed of.

Not so long ago, the phrases ‘self-published’ and ‘successful author’ were considered mutually exclusive. An air of superiority permeated the literary world, with self-publishing the refuge of those either wealthy or gullible enough to fund their passion projects themselves. Serious writers didn’t self-publish, and serious readers didn’t buy books unless they bore the imprimatur of the serious publishing houses. The internet, with its flattening, do-it-yourself ethos, has changed all that. (Indeed, it’s hard to think of an industry that’s been disrupted more by the internet than publishing.) Publishing houses, and the literary agents that serve them, have lost much of their power, leaving self-made writers like Rogers to claim large readerships of their own making.

But the internet did more than connect writers with readers; it opened up a two-way line of contact between them. Rogers values online reader reviews, especially the negative ones, which he sees as an informal creative writing degree. “I’m getting feedback in real-time about what works for my books and what doesn’t. And that’s enabled me to find out very quickly what my flaws are. I’m very focussed on improvement.”

On the other hand, positive reviews and other metrics like sales and page-read statistics allow Rogers to make creative decisions based on what his readers want. His first novels focused on the adventures of Jason King, but over time his literary universe has expanded organically. Will Slater, a supporting character in those first few novels, got such a positive response from readers that Rogers gave him his own spin-off series. The most recent addition to Rogers’ oeuvre is the double-headliner ‘King and Slater’ series, in which both lead characters team up.

When Rogers has finished writing for the day, he picks up a book he admires and begins transcribing it word for word.

This action in Rogers’ novels is set in a self-contained world, with characters referencing each other across books. “It’s all in-universe—sort of like what Marvel does, where everything is connected in some way,” he explains. For fans, the braiding of characters and events between books is a satisfying structure. But there’s a commercial logic to the coherence as well. “Each book that I release now is almost like an ad for my entire catalogue,” he says, demonstrating the commercial nous that turned him into a millionaire by the time he was 20.

Rogers isn’t the only self-published author making serious money from Kindle Direct Publishing. At the end of 2020, he appeared in an ad for KDP with fellow Australian author C. J. Archer. Archer, a former technical writer who also lives in Melbourne, began writing and self-publishing historical fiction in 2011. She has since sold almost two million copies of her books, half of those through KDP.

Both Rogers and Archer are genre writers, which isn’t a coincidence. Genre books—romance, fantasy, sci-fi, and so on—rule the Kindle charts for the simple fact that genre fans tend to read far more in volume, and care far less about publisher prestige, than readers of so-called literary fiction.

Even in the traditional publishing sector, genre writing sells more than literature. But there are also incentives that favour genre writing baked into the Kindle publishing system. Rogers makes more than half of his income through Kindle Unlimited, a subscription service that charges users a monthly fee to read as much as they want. Amazon tracks what they read and pays the authors per page.

A major objection to this system is that it tends to reward certain books over others— namely long-running fiction series and self-help books, otherwise known as easily digestible page-turners. Anything more taxing can find itself at a disadvantage; it’s unlikely, for example, that the James Joyce estate would have banked as much from Ulysses if royalties were based on pages actually read.

But Rogers is quick to point out the advantages of the arrangement. “It can be easy to market something falsely and get a quick sale,” he says. “But I want someone to start reading my books and be compelled to finish them. I love that it incentivises me to get better at my craft.” And it seems his readers feel the same way. Across the world, Kindle Unlimited users read around 150,000 pages of Rogers’ e-books every single day, which accounts for about half of his income.

Rogers says Amazon's pay-per-page model has improved his writing. "It incentivises me to get better at my craft."

Rogers' business savvy is impressive. But it would count for nought if he couldn’t also spin a tale; to be a professional writer, at some point you actually have to write. To this end, he often engages in unorthodox techniques to make up for his lack of formal training. When Rogers has finished writing for the day, usually around noon, he picks up a book he admires and begins transcribing it word for word. It’s a practice he took up two years ago when he became immersed in the works of his favourite author, the crime and mystery writer Don Winslow. “I was reading his stuff, and I just couldn’t understand how it was so good,” Rogers remembers. “So I transcribed one of his novels, writing out 2,000 words of it a day. And something just stuck up there.”

Since then, he’s transcribed from one of his favourite books every day, writing out 12 full-length novels in their entirety in just two years. “I see it as a deeper form of reading”, he says of the method. “When I then go to write my own books, I can’t remember anything specific from what I’ve transcribed. But somehow I just have a bigger toolbox to get down what I want to get down. It’s weird that I sink so much time into transcribing when I can’t narrow down exactly what it does. But I know that it works.”

When he’s not working on his writing, he can often be found watching mixed martial arts. It’s a hobby that bleeds into his thrillers. “It’s like watching physical chess,” he says. “A decent chunk of my books are action scenes, and it helps me so much with describing every little facet of what’s going on in a fight. I’ve been able to pick up when other authors don’t understand the nature of fight scenes and what’s really going on.”

From the outside, all the running and fighting might look like the excesses of someone whose career is so turbo-charged they only need to work two hours a day. But for Rogers, the exercise is the work. “It’s all me trying to figure out my own brain and what’s going to get work done,” he says. “I’m only 24. It’s strange being so young and not having anyone there to say, ‘This is what you’ve got to do and this is when it’s got to be done by.’ It’s difficult to navigate at times.” (Rogers’ only literary collaborator is his mum, who has proofread all his books.)

He tells me it’s unlikely he’ll work with a traditional publisher in the foreseeable future. Any deal “would have to be incredible”—under the terms of a conventional contract, he’d make far less money per book than he does self-publishing. A traditional contract would also slow his pace; in the time it takes a publisher to approve edits, design the layout, print and then distribute a single title, Rogers could have released four novels.

For now, he intends to carry on along the path he’s forged for himself. “I love writing thrillers. It’s what I would do even if there was no audience in it. I honestly wouldn’t want to write and release books slower than I’m doing it now. The market wants it. But it’s also the way I’m wired.”