The poet laureate of Amazon

He was one of Amazon’s most prolific product reviewers. But when Kevin Killian died in 2019, he left behind something closer to literature than shopping advice.

Illustration by Susie Ang

Before they became infested with bots and AI-scripted astroturf bullshit, internet user reviews were already controversial.

In the mid-1990s, a charming little store called Amazon discovered that you didn’t actually need a proper marketing department. You could harness the unpaid labour of millions of customers by encouraging them to leave reviews of various products online—for free. Toasters. Books. Defibrillators. Prefabricated houses. People would, for some reason, willingly donate their time and energy to rate things on a five-star scale and not expect a penny in return. Which was good, because Amazon was not in the business of handing out pennies.

Today we know Amazon as a cartoonishly dystopian megacorp whose $2 trillion market cap is comparable in size to the economy of South Korea. But among all the accolades and epithets assigned to Amazon—inventor of modern e-commerce, winner of the internet, algorithmic surveillance nightmare, accelerationist endpoint of anarcho-capitalism—there’s one people often leave out: accidental patron of the avant-garde.

Between 2004 and his unexpected death from chemo complications in 2019, the American poet and author Kevin Killian wrote an estimated two thousand and four hundred product reviews on Amazon’s user-generated review system. Rough word count: more than a million.

We say ‘estimated’ because Amazon doesn’t archive its reviews forever, so it’s hard to quantify the exact volume of his output. But there are people who have tried. Fearful that Killian’s legacy might vanish into the void, a man named Will Hall compiled Killian’s remaining reviews into a monstrous three-thousand-page, single-spaced PDF. A selection of these reviews has recently been collated by LA publisher Semiotext(e) in an actual book, wisely titled Selected Amazon Reviews. Six hundred and fifty pages. Yours for the low-low price of $32.95. Available at all good soulless multinational retailers.

If you’re wondering why a publisher might compile someone’s Amazon user reviews into a book and then expect people to buy and read that book, the answer lies in Killian’s prose. While he technically wrote product reviews, his work tended to be less buy-this-electric-apple-coring-machine and more underground art project—part diary entry, part long-form prose poetry, part fictional biography. Think David Sedaris meets choice.com.au. The Roger Ebert of everyday stuff, if Roger Ebert was an avant-garde poet who sometimes made things up because life was more interesting that way.

“Kevin wrote thousands of Amazon reviews,” his long-time partner Dodie Bellamy said in a previous Killian anthology, “subverting and reinventing the genre, queering the divides between fact and fabrication, between spoof and serious critique. In the process, he perverted Western rationality into a carnivalesque What the Fuck.”

Killian told various, often contradictory, versions of how he came to write for Amazon. But they all start the same way: with a heart attack.

In Killian’s reviews, what starts as a simple film synopsis might then turn into a detailed biography of Geraldine Fitzgerald, or musings on the hotpants of Kylie Minogue. A four-star review of Pilot pens is told from the perspective of an American boy growing up in France, while a review of baby food fuses product descriptions (Killian praises the “soft, piquant flavor”) with an unsubstantiated health claim about “feeding an infant a tiny amount of dirt every day.” Product descriptions intertwine with narratives, some plausibly real, others patently false.

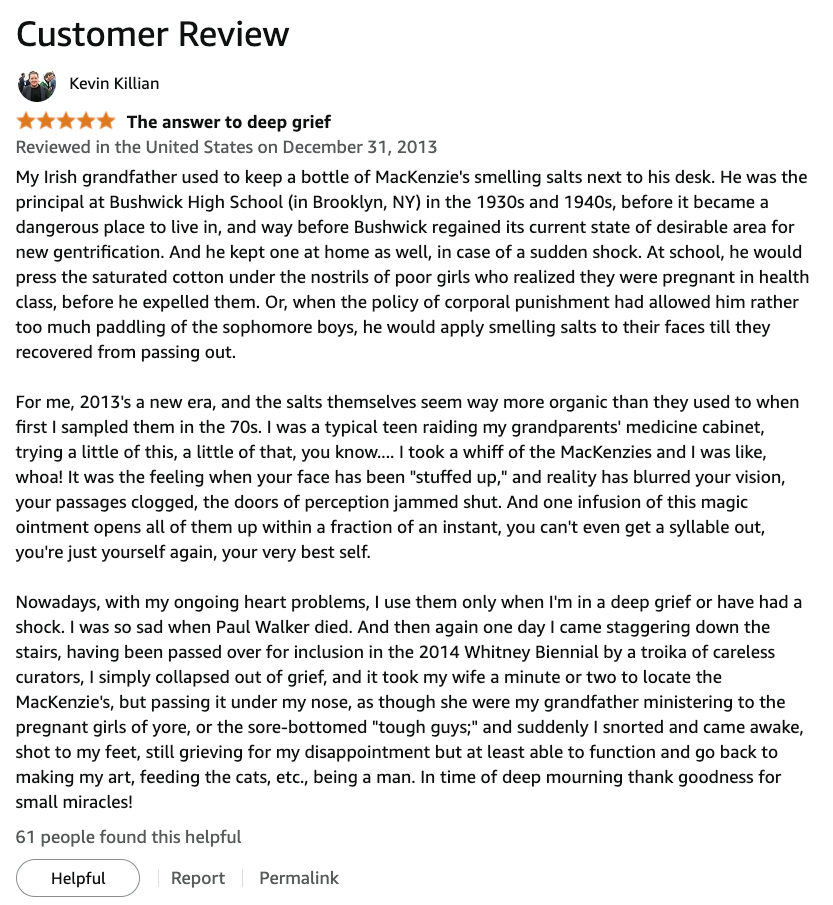

Take his review of MacKenzies Smelling Salts, titled “The answer to deep grief.” It begins innocuously enough: “My Irish grandfather used to keep a bottle of MacKenzies smelling salts next to his desk.” But then Killian veers into darker territory, revealing that his grandfather, a high school principal in the 1930s, used the salts to revive boys who’d passed out from his overzealous paddling. From there, the review ping-pongs through time—“For me, 2013’s a new era, and the salts themselves seem way more organic than they used to”—before landing somewhere more personal and melancholy: “With my ongoing heart problems, I use them only when I’m in deep grief,” he writes, listing among his sources of sorrow both the death of actor Paul Walker and being passed over for inclusion in the Whitney Biennial.

Seemingly without trying, Kevin Killian had invented a new form of storytelling, and he kept it in pieces, scattered to the four corners of amazon.com. You wouldn’t necessarily read his reviews to buy a better toaster—he thought the fundamental premise of criticism, man’s never-ending search for the ‘best’, was hubristic and kind of dumb—but rather for the same reason you might listen to music, or read poetry, or appreciate an oil painting.

Not that Killian cared about lofty esoteric art talk. Like many writers, he wrote because the idea of not writing just didn’t feel right, like living with a splinter under your skin. “The concept of user-generated content has been the dirty secret at the bottom of many internet-related practices,” he told an interviewer in 2013. “They call it UGC, like an acronym for some hideous drug. Basically it’s unpaid labor, and basically it’s what’s put freelancers (like you?) out of business, or scrambling for the next paid gig. I can see why you hate me.”

Over the years, Killian told various, often contradictory, versions of how he came to write for Amazon. But they all start the same way: with a heart attack.

Kevin Killian was born in the town of Smithton, New York, in December, 1952. He was raised Roman Catholic. As a child, he became New York City Spelling Bee champion. As a young man, he attended Fordham University, a Jesuit research university in NYC.

In the ’80s, he moved to San Francisco and penned several novels that were well received by the few people who bothered to read them. He was active in LGBTQ+ circles and helped pioneer San Francisco’s famous New Narrative movement, along with writers like Robert Glück, Bruce Boone, Kathy Acker and Dennis Cooper. For the New Narrative-ists, authenticity was everything. Subjective experience didn’t need a filter. The whole idea was to blur the line between fiction, autobiography and criticism, ditching traditional storytelling for more fragmented, experimental stuff. Michel Foucault was a big inspiration, to give you an idea of the kind of sandbox Killian was playing in.

In Killian’s case, all this highbrow theory was mixed with a mind like a razorblade, a generous scoop of satirical wit, and a dash of freewheeling absurdity. Then came 2003, and a massive heart attack.

“I had a heart attack,” he wrote in 2006, “and the doctors put me on a regimen of drugs so strong that it was like my mind had been removed and I was only happy. I couldn’t find my way to the end of a sentence, just drifted off, continuously happy, like a warm heroin or mescalin high.

“Thus I gave up on writing, reasoning that I had done a helluva lot of writing already, had a small shelf of books nobody really gave a fuck about anyhow. Maybe it was time to hang it up and rest on my laurels. I spoke the word out loud, ‘ex-writer.’ And I was fine with being one, for about a year.”

A year later, so one story goes, the poet Rodney Koeneke bought Killian a detective novel. For whatever reason, Killian decided to write down his thoughts on the book and publish them on Amazon. By April, 2004, he was reviewing books and movies every day, often twice a day. “It’s surprising how many texts you can actually experience in a lifetime, or say, in the span of a year,” he wrote. “This was my regimen. My therapy, if you will.”

Slowly but surely, like a stroke survivor learning to regain mobility, Kevin Killian became a writer again. Not in any official capacity, at least not in the beginning, but in the purely literal sense: he was a dude who wrote. A lot. Just on Amazon.

Killian's review of MacKenzies Smelling Salts

In the beginning, Kevin didn’t really tell anyone about his reviews. He was happy for them to live semi-anonymously, floating out there in cyberspace. But soon people began to notice his prolific output, and the editors of Hooke Press offered to publish a small selection as a kind of anthology. “I would have done it differently,” Kevin admitted later, “but that’s the great thing about selection, as I learned long ago, walking the seashore with my grandfather, and he’d pick up the shells I discarded, and I only liked the ones he didn’t. The day we both wanted the same abalone or whatever is the day I stopped doing it with him.”

The beauty of Kevin Killian’s reviews has something to do with the contrast between the message and the medium; between the funny, thoughtful, large-spirited words and the late-stage hellscape that Amazon was morphing into during the early 2000s. He could have published his thoughts anywhere, but he chose to write them down on the most capitalist platform money could buy. A website that bears the same relationship to literature as Tinder does to human love. It’s the equivalent of a punk art collective taking over a Walmart or something.

Dodie Bellamy described her late partner’s reviews as “a ritualistic, disciplined quest through the wasteland of rabid consumption.” And there is something quest-like and kind of noble about the whole thing. Amid the slurry of online opinions, swamped by waves of hate and shallow consumerism, Killian’s writing feels honest and real, like running into an old friend at a Costco. Never mind that much of it was fiction, or that his product descriptions could be as fanciful as the characters he conjured to write them. It helps that he was clearly smart as heck, surprisingly funny, and had an encyclopaedic critical knowledge of everything from gay erotica to mid-century cinema.

“The obvious philosophical problem is that I was doing this without being paid, in the service of a huge multinational corporation that was killing bookstores and perhaps writing itself,” Killian once told an interviewer. “But some defended me and said, ‘He’s torqueing the system from within; they’re not actually reviews, they’re poems,’ so it was a poetic project.”

It’s hard to find an analogue for Killian’s weird Amazon opus. If you had a whiteboard handy, and felt so inclined, you could probably draw a line between him and ‘fragmented literature’ behemoths like James Joyce’s Ulysses and TS Eliot’s The Waste Land. But maybe Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa is a better comparison. Following his death in 1935, a trunk (now known as “the ark”) was found among Pessoa’s effects. Among other things, it contained twenty-five thousand pages of manuscripts, notes, fragments and diary entries, mostly written on scraps of paper. Eventually these would be compiled into a book, called The Book of Disquiet, which was first published in 1982.

The Book of Disquiet is sometimes described as “the diary of a dreamer,” and that’s a pretty good description for Killian’s body of work. His Amazon reviews channel the spirit of the Objectivist poets, like William Carlos Williams, who famously said, “No ideas but in things.” Between 2004 and 2019, Kevin Killian took thousands and thousands of things—ordinary forgettable things—and turned them into ideas. Then gave them away for nothing.

For what it’s worth, I give Selected Amazon Reviews five stars.