Want to save the world? The ‘Robin Hood of public relations’ has some ideas.

Conservatives have long dominated the political battlefield with simple slogans (and simpler thinking). PR legend David Fenton, whose campaigns helped reverse the nuclear arms race and end apartheid in South Africa, says it's time the left did the same.

Photo illustration: Emily Thiang/David Fenton archives

Earlier this year, shortly before January 26—a day you might know as Australia Day or Invasion Day, depending on your politics—Australia's opposition leader, Peter Dutton, launched a quixotic and short-lived campaign, calling on the nation to boycott Woolworths.

The supermarket’s crime, Dutton said, was refusing to stock Australia-themed merchandise in the lead-up to the country’s national day. Never mind that no such refusal had taken place; according to Woolworths, they had stopped stocking the merchandise because no one was buying it.

Ordinarily one might assume the Liberal Party would back the capitalist logic of supply and demand. But for Dutton and his ilk, not being able to buy an apron with a Southern Cross on it was proof that woke politics had infiltrated our largest supermarket chain. A line had been drawn; the silent majority needed to show them that it would not stand.

As with many of the broadsides from conservative politics—from Scott Morrison’s “war on the weekend” to Tony Abbott’s “stop the boats” (to John Howard’s “stop the boats”)—“boycott Woolworths” was a slogan in search of a cause, an empty vessel into which a certain part of the political demography could pour their grievances.

But for more than a week, that slogan dominated the national conversation, amplified by a biddable media and well-funded lobbying outfits like Advance Australia. Was Woolworths anti-Australian? It was an issue wholly without substance, about which both politicians and public suddenly needed to take a stand.

We have become so inured to the ways in which conservative forces dictate the political narrative that we tend to write them off as some intrinsic fact of life. Fear speaks louder than hope, after all, and humans will always try to protect the status quo. But conservatives aren’t just tapping into some primal facet of human nature; in many ways, they’re also harnessing the simple tenets of advertising—techniques and strategies Don Draper-types have been using since the 1950s to manufacture desire for products that don’t yet exist. In the immortal ad man’s words, “If you don't like what's being said, change the conversation”. What if all progressives really need is a better marketing department?

At its most fundamental level, marketing is about creating ideas that prompt action. A sceptical and advertising-weary public may assume that any old idea can be sold to us. But as any marketer can tell you, for an idea to work, it first needs to be built around something “true”.

True in this case is less a question of factual or statistical truth, and more about unearthing some fundamental aspect of human psychology or behaviour. Apple’s legendary 1997 ‘Think different’ campaign—largely credited with reviving the fortunes of the then-flailing company—didn’t tell you anything about the qualities of the Mac as a desktop computer. Instead, it used Apple’s position as an underdog to sell the idea that the Mac was the natural choice of renegades and freethinkers.

So it goes with politics. We may deride the empty sloganeering, but slogans define the story of a political moment—and the conservative side is clearly better at exploiting these repeatable memes for their own ends.

This state of affairs isn’t news to David Fenton. A legendary figure in PR, advertising and progressive politics, the ‘Robin Hood of public relations’ has spearheaded some of the most successful left-wing campaigns of the last fifty years, from the movement for nuclear disarmament to ending apartheid in South Africa and legalising cannabis in his homeland, the United States. Across his career, Fenton has been singularly preoccupied with the question of how to best drive social change and why the right so often ends up controlling the narrative.

“A lot of conservatives go to business school,” Fenton explains down the line from his New York City office. “And they learn marketing, and cognitive science, and they have to sell products and services to advance their careers. So they have a natural inclination to pay attention to and consciously affect public opinion.”

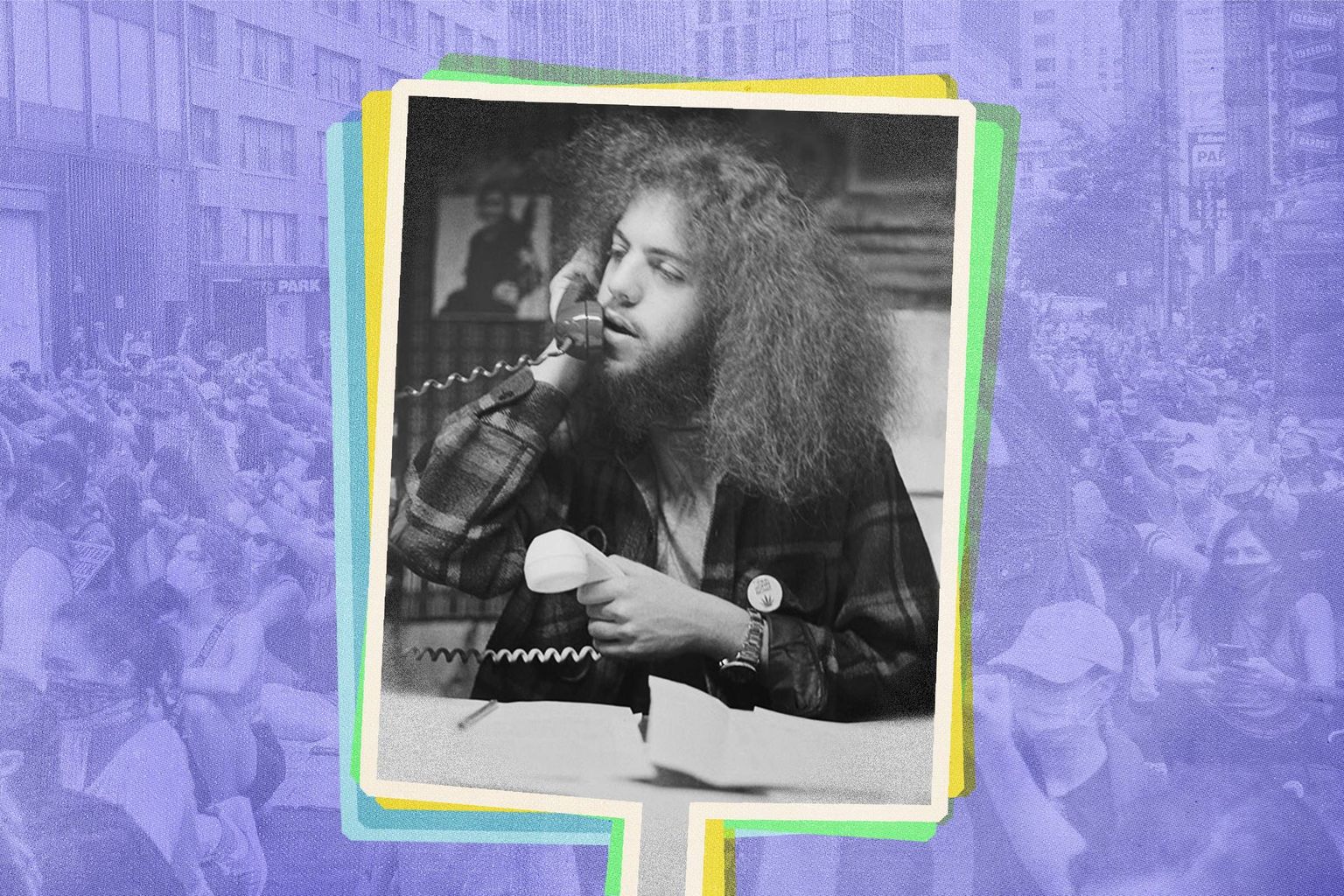

A high school dropout, Fenton joined the counterculture movement of the 1960s and became one of its pre-eminent photographers. Documenting this time of social upheaval and rapid progressive change left him with an enduring feel for the importance of imagery and messaging in revolutionary politics—an insight he would channel into his later work as public relations director at Rolling Stone magazine, and then into the social and environmental work he pursued at his own firm, Fenton.

The gains made by the civil rights and anti-war movements in the ’60s and ’70s were sweeping, especially compared to the conformist mood of the previous decades. But success breeds complacency, and Fenton now sees the left in thrall to what he calls the “Enlightenment fallacy”—a misplaced belief that if we simply present the right facts to people, we’ll shift the agenda through the cleansing force of reason.

Fenton, photographing a police raid on a commune in 1971. Image: David Fenton archives.

A slightly squarer Fenton with Nelson Mandela in Washington, D.C., in 1990. Fenton oversaw Mandela's first U.S. press tour while working to pass sanctions against apartheid-era South Africa. Photo: David Fenton archives.

“Many people that study the sciences and law and the humanities have this attitude that their ideas are intrinsically brilliant, and they should self-replicate because of that sheer brilliance,” Fenton says. But the harsh truth, he says, is that facts don’t work. At least not by themselves. “But when they’re embedded in storytelling that hits the heart and speaks to our moral frameworks? Change can happen.”

Fenton cites Trump's Make America Great Again as an example. “Hearing that might make you want to vomit,” he says, especially if you’re allergic to facile sloganeering. But it works precisely because it’s facile. “You have to simplify your messages, and then you have to ensure they reach the right audience with sufficient repetition to sink in and change consciousness.” Once you’ve done that, he says, behaviour and voting patterns will follow suit. But first you have to become a broken record. “People don't learn unless things are repeated till you’re nauseous hearing it. That’s just science.”

Now 71, Fenton has narrowed his life’s work to a single pursuit: climate change. After selling his PR firm to commit fully to the cause, Fenton has immersed himself in the thick of environmental advocacy. It’s where he feels he contribute the most good. But it’s also the arena in need of the most help. To his mind, no issue highlights the left’s inability to craft a compelling narrative more than the mess of the climate movement.

“When you ask Americans what causes climate change, the number one answer you get is the ozone hole. And when you ask them how to solve climate change, the number one answer is reduce, reuse and recycle. And obviously neither of those answers is correct.” They might be wrong, but the fact that both ideas are top of mind for so many people is a testament to the effectiveness of their campaigns, which successfully embedded themselves in the public psyche through the power of simple messaging and constant repetition.

To Fenton, the fundamental problem is that most of us don’t properly understand what we’re doing to the Earth—and those that do don’t understand how to explain it in an emotionally resonant way. “We better fix that,” Fenton says, “because it’s really hard to mobilise people against a problem they can’t describe, don’t hear about and don’t understand at all.”

He points to pre-election surveys in the U.S. that show climate change as one of the least concerning issues for voters. “We have failed to explain to people how climate change is an imminent threat to the things they do care about—their property and their kids and their health and their security and their jobs and their ability to buy insurance.”

This is a massive propaganda war. But only one side is on the battlefield.

“There are plenty of conservatives that would like to protect the future too, but they don't know it’s at stake.”

Fenton’s latest project seeks to right this balance by exploiting another maxim of marketing: relatability, or making sure the right voice is speaking to the right audience. And that means using the conservative echo chamber’s media apparatus against them.

“If the only information reaching a population is that climate change is BS, or that it’s some plot to install liberal totalitarianism, then how can you expect them to think anything else about it?” he asks. The only solution, Fenton says, “is to have people from their own tribe tell them how climate change is going to mess with the things they care about”—their kids, their health, their golf courses, and so on.

To do this, Fenton started working with personalities on the right to frame the challenges of climate change in language that would appeal to a Fox News audience. “We made videos where conservatives talk to conservatives about how climate change threatens conservative values like freedom, prosperity, security and health,” he says. In one, an evangelical climate scientist speaks about how her Christian faith animates her drive to fight climate change. In another, a retired Army general discusses the threat of rising sea levels to overseas U.S. military bases.

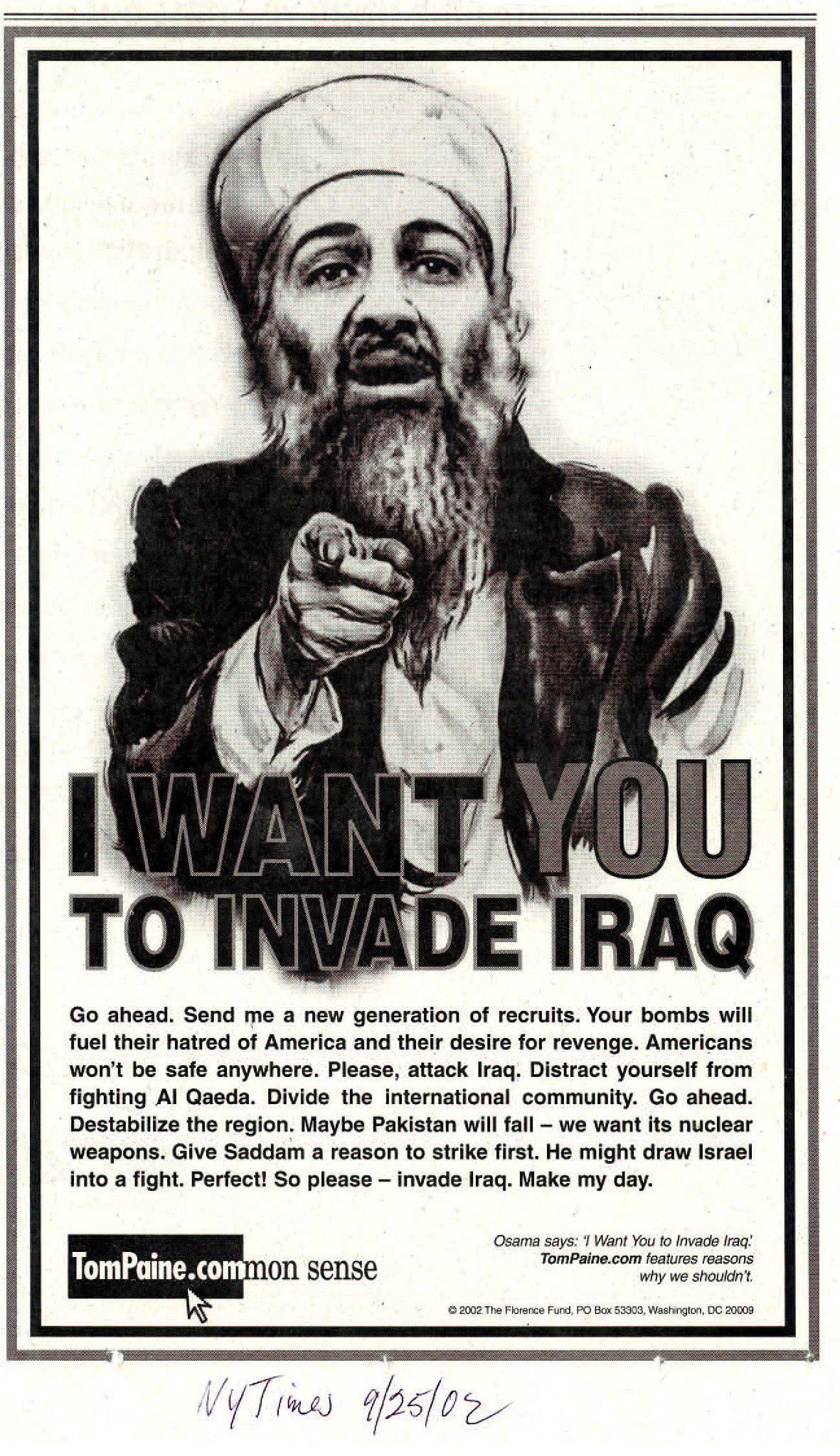

Left: Fenton's 2002 ad against the Iraq War ran in the New York Times, before being picked up by Rolling Stone and Der Spiegel. A print-out was later read by senators at the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Equipped with this content, Fenton and his team used Facebook’s audience tools to target the videos at right-wing users in particular congressional districts, and then hired a Republican polling firm to measure the results. “Lo and behold, it worked. Exposure to these videos in that target audience—moderate conservatives, not the rabid, crazy people—shifted their attitudes about whether climate change was real and whether we had to do something about it by a significant amount.”

Working with researchers at Yale, Fenton and his team had the results peer reviewed and published in Nature Climate Change. With success quantified, they secured more funding and are now expanding the campaign into additional districts, as well as buying occasional ads on Fox News.

Of course, running ads on Fox News isn’t cheap. Which points to another marketing truism: you need budget to shift the dial.

Unfortunately, when it comes to the actual grunt work of policy messaging, budget is in often in short supply. “If a climate organisation receives a million dollars, how much of that is it likely to spend on marketing and communications?” Fenton asks. “It’s tiny: less than one per cent, and most of that’s for fundraising.”

To Fenton, these simple economics are at the reason why we haven’t yet created a climate campaign that matches the urgency of the problem. “We already have enough science,” he says. “We have enough policy. But we don't have enough demand for change. We know how to create demand, but there's not a lot of funding for that kind of work.”

Some might raise an eyebrow at the sight of a campaign man arguing for more campaign funding. But if Fenton is worried about the optics, he doesn’t show it. “This is a massive propaganda war,” he says. “But only one side is on the battlefield. Our community doesn’t make a priority of public communication, and that means we don’t fight back. But we need to fight or we will lose.”