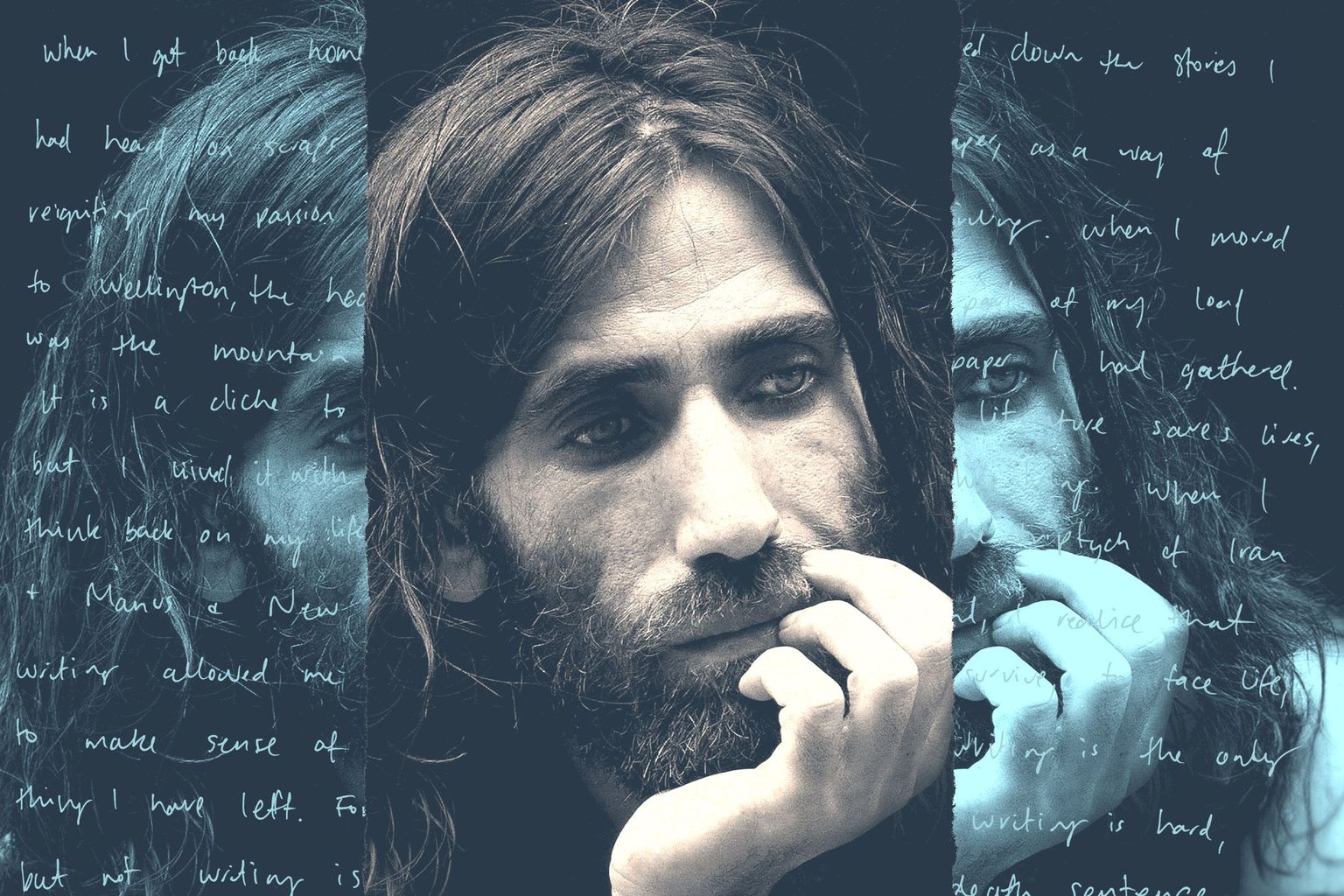

A prison island. A smuggled phone. Behrouz Boochani on the writing that saved him.

Four years after his incarceration on Manus, Behrouz Boochani reflects on the writing that helped him hold onto life in prison—and to make sense of it after.

Photo illustration: Emily Thiang

Six years. That’s how long Kurdish journalist Behrouz Boochani would end up imprisoned on Manus Island, the offshore detention camp set up to deter refugees from seeking asylum in Australia. Determined to tell the world about the cruel reality of life on Manus, Boochani began writing about his experiences on a smuggled phone—first in dispatches for The Guardian, and then in the genre-bending memoir No Friend but the Mountains. That book would go on to win Australia’s most prestigious literature award while Boochani was still imprisoned, turning him into a cause célèbre on the world stage. Five years after its release, Boochani reflects on the writing that helped him hold onto life while in prison—and then to make sense of it afterwards.

In Iran

The Italian novelist Italo Calvino begins his novel, If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, with an unexpected scene. The narrator asks his readers to settle in their most comfortable positions before opening the book. He suggests reading on a sofa, a chair, at a red light, in an office, lying prostrate or supine. He goes as far as to say that if one is most comfortable on the back of a galloping horse, go for that.

When I think about these lines, I find the last image an apt metaphor for writers working in Iran. If you are a writer there, you always have to work on the back of a galloping horse. Being a writer in a country ruled by a religious dictatorship is an unpredictable, difficult ride. It’s not just because everything you write has to be run through the absurd machine that is the censorship office, or because of the poverty and isolation central to the life of anyone choosing this path. It is mainly thanks to the sense of being constantly, relentlessly reined in.

This is especially the case for someone like me. I am a Kurd, and the Kurdish language is excluded from all the official platforms, the media, and the entire education system in Iran. Any attempt at rejuvenating Kurdish or simply keeping it alive is treated as a security threat. I left my hometown, the city of Ilam in the west of Iran, in May 2013, for reasons that had to do with my native tongue. A group of friends and I published a bilingual magazine named Vorya in Kurdish and Persian, dedicated to recording and preserving the Kurdish experience. We wrote for the people of Ilam, bringing their attention to their identity and their language, warning them against sleepwalking through the loss of their culture.

Back then, nobody knew me. I had written some scattered stories and poems, but journalism was my focus, and my goal was to do something for the Kurdish people of Iran. We knew they would come for us, and yet that prospect never deterred us. My friends and I put together a few issues, paying the costs out of our pockets.

Sure enough, one day they came. They stormed our small office, took everything and arrested six of my friends who were there that day. I went underground, and a month later left Iran. I got to Indonesia and, with other Iranian refugees, boarded a boat for Australia.

In Manus

After our boat was intercepted, I was transferred to Manus Island. Life in the camp was brutal and somewhat surreal, unlike anything I had experienced. Everything was forbidden on the island and we could own nothing but the loose, bland clothes they gave us. There was no music, no pen and paper, not even a ball to kick around.

I saved all my cigarettes for months and bribed one of the guards to bring a cell phone into the camp. That phone became our sole means of communication with the outside world. I managed to build relationships with journalists and human rights organisations, but the most important and meaningful connection I had was with the poet Janet Galbraith. Corresponding with her was a lifeline that kept me attached to literature, ; the only way I had to remind myself that, first and foremost, I was a writer. Not out of vanity or self-importance, but because I needed that reminder to survive.

Prison life was a daily exercise in humiliation. We were cursed at and insulted all the time, forced to stand in the tropical summer for hours to get food. We were referred to by our numbers and treated as subhumans. In such circumstances, it was vital for me to remember that I was a writer, which was my way of remembering that I was a human being, that I had dignity, and if I wrote, there were people outside that island who would read and respect me. My image of myself as a writer fortified me, enabled me to see myself beyond the prison and its draconian laws and violent rules.

Over the first years, following my journalistic instincts, I took notes all the time. Those notes became the basis for my first book, No Friend but the Mountains. For me, literature was not merely a matter of aesthetic expression but a tool that empowered me to challenge the prison and its rules and, beyond that, the politicians who consigned us to that camp. For me, literature was not merely a matter of aesthetic expression, but a tool that empowered me to challenge the prison and its rules, and beyond that, the politicians who consigned us to that camp. Writing was my way of overcoming isolation, creating a space in which the humanity of myself and my fellow refugees was acknowledged.

I imagined my words as a flock of birds embarking on a nocturnal flight from our tiny island to the bigger one named Australia.

As time went on, I grew increasingly confident that, through writing, I could resist the systematic dehumanisation and torture I underwent in the camp. Was I writing on horseback? I think I was, this time not just because I was being controlled, but also because of the very conditions in which I wrote.

That little phone I had smuggled in was my only writing tool. Most of the time I wrote at night. I was sharing a cell, which had a small window, with three other refugees. We had covered this window with a blanket, but still, when I turned on the phone at night, the guards would notice a slight brightness in our room that seeped out through the fibres of the cloth. So I had to go under another blanket on my bed and write. I did it so often that it became my office, and I would go there to write even when I didn’t have to. I lost my phone twice in those years, after the guards kicked the door open for a surprise search and snatched it out of my hand before I had time to hide it, and I had to wait a long time to find a new one.

Over time, as I wrote more about the prison, my understanding of it deepened and I learned to appreciate my fellow refugees. In the fourth year, I felt that I knew enough and had enough material to write a book. The camp was so packed it was impossible to work consistently without interruption during the day, so I set a routine of writing from the sleeping hour to midnight under my blanket. I wrote the book as a series of long WhatsApp messages, which I sent to my friends and my translator. After pressing send on a message, I imagined my words as a flock of birds embarking on a nocturnal flight from our tiny island to the bigger one named Australia. This is how my first book got written.

Six years and two months after I arrived in Manus, I managed to secure a visa for New Zealand and I landed there. Now that I look back on that time in the camp, I see myself as someone who did nothing but write.

In New Zealand

In New Zealand, everything was set up for me. I had an office at a university, access to the library, time, space. But I couldn’t write a word. I felt like an egg thrown from a boiling pot into a jug of cold water, half-boiled.

After my body had left the camp, that life haunted my dreams. I never had nightmares on a regular basis before, not even in Manus. In New Zealand I woke up every day in a nice house in a beautiful city and couldn't do anything but think about my bad dreams. First I tried to get rid of them by writing them down, but that pulled me even deeper into the past. I felt like I was walking in the air, and every second I anticipated a fall. I tried hard to write but my mind was empty. My nightmares became like dominoes, each setting off the next one.

This limbo lasted about a year. Then the nightmares began to subside. Towards the end of the second year, they were like flies in the room. I could live with them as long as there weren’t too many of them.

To avoid isolation, I left the house every day to see someone, in the university or in the park or at the gym. I jumped at any chance for a conversation. When I got back home I jotted down the stories I had heard on scraps of paper, as a way of reigniting my passion for writing. As I wrote other people’s words, I felt inspired to make up things to supplement them.

When I moved to Wellington, the heaviest part of my load was the mountain of paper I had gathered, all the little stories I had written. The story of the man who sees the same mysterious, beautiful bird wherever he goes. The bird is alone, non-native to New Zealand, and the man has known it since his childhood. Only after the bird disappears from his life does he kiss a woman for the first time. The story of a man riding his bike along the river, noticing the young version of himself on a canoe pedalling downstream. He is so terrified he runs home and stays put for days. To overcome this terror, one day he rents a canoe and takes it to the river to face himself. He keeps pedalling without seeing the young version of himself until he ends up in the middle of the ocean. Or the story of an old lady, a retired midwife who loiters at street corners and recognises the people she delivered years ago, though nobody recognises her.

I was writing these little anecdotes and tales without attaching any literary significance to them, without acknowledging that I was engaging in the act of writing. It is such a strange life to be a writer. When you are conscious of writing, it can feel like torture, like a gradual death. When you think you are just putting words down without taking it seriously, it can be the easiest thing in the world.

It is a cliche to say literature saves lives, but I experienced it with my whole being. When I think back on my life, in the triptych of Iran and Manus and New Zealand, I realise that writing allowed me to survive, to face life, to make sense of it. Writing is the only thing I have left. For me, writing is hard, but not writing is a death sentence.

Text translated by Amir Ahmadi Arian.