India’s street kids were tired of being ignored. So they started a newspaper.

Their reporting on police brutality, malnutrition and child labour has changed lives. The newspaper they work for has changed theirs.

Photo: Mansi Thapliyal

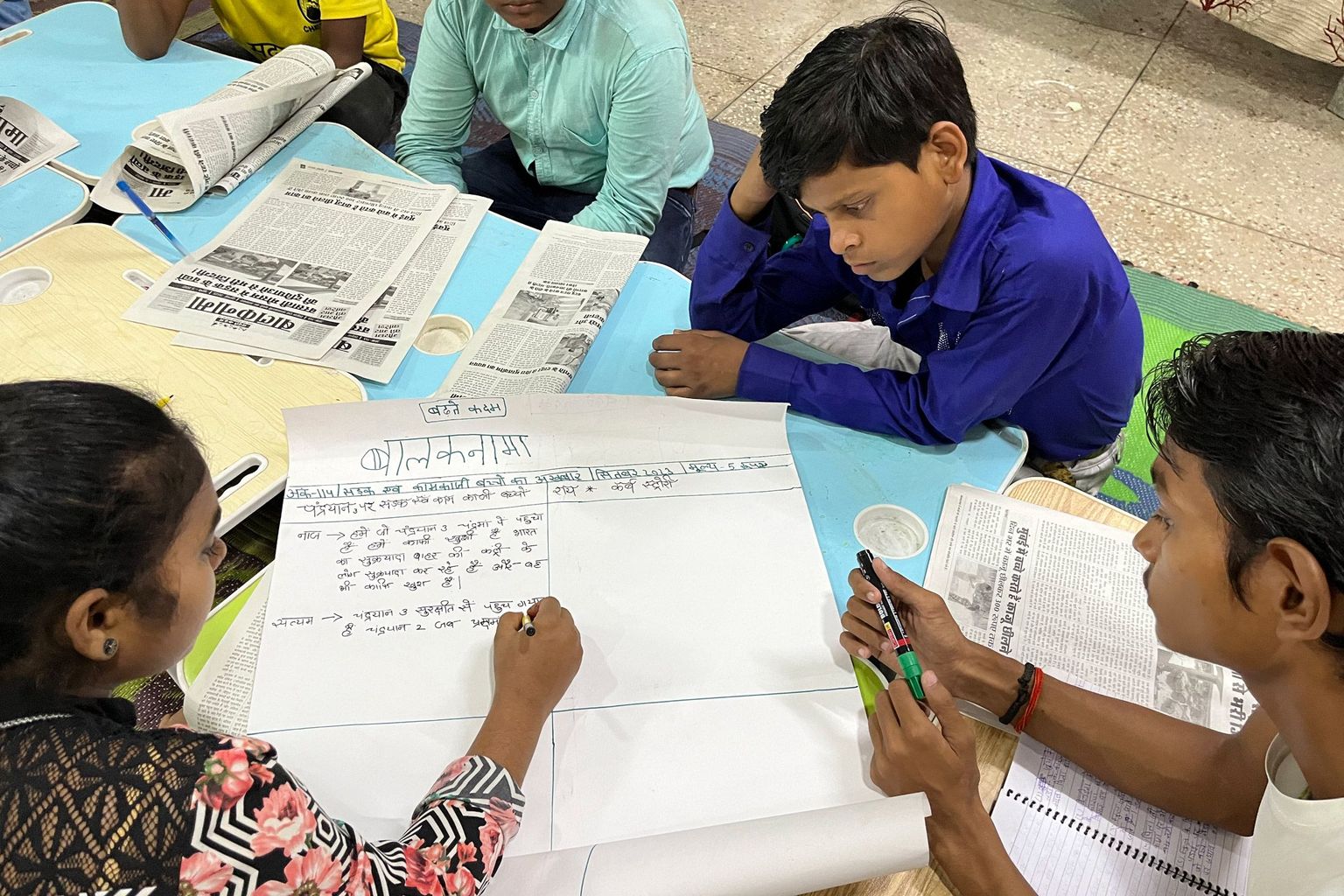

It’s a hot morning in Delhi, and Kishan Rathore is busy. This in itself is hardly unusual for a newspaper editor. But today is the paper’s monthly editorial meeting, and Rathore’s newsroom is abuzz. One by one, reporters pitch their ideas for the next issue while their colleagues debate their newsworthiness—a trial-by-fire that separates the journalistic wheat from the chaff. Some ideas are shot down; others are put on the back burner should something more newsworthy fail to emerge. And then comes a story that blows the rest out of the water.

There is a slum on the outskirts of Delhi, the reporter says, whose residents have to walk two kilometres every day to fetch water. So far, so-so: as dire as that sounds, people in some parts of India have to walk much further. But then comes the twist: this particular slum is actually surrounded by water connections—the slum-dwellers just aren’t allowed to use them.

Rathore writes something down on a large flip chart. The story is in.

Conversations like this happen every day in newsrooms across the world. But this is no ordinary newspaper. Run out of a basement in Delhi, Balaknama focuses exclusively on stories about India’s street kids—the 18 million minors who live and work on the streets in varying levels of poverty. As newspapers go, it’s a notable point of difference. But what truly sets the paper apart is its hiring policy: its reporters themselves are all street kids.

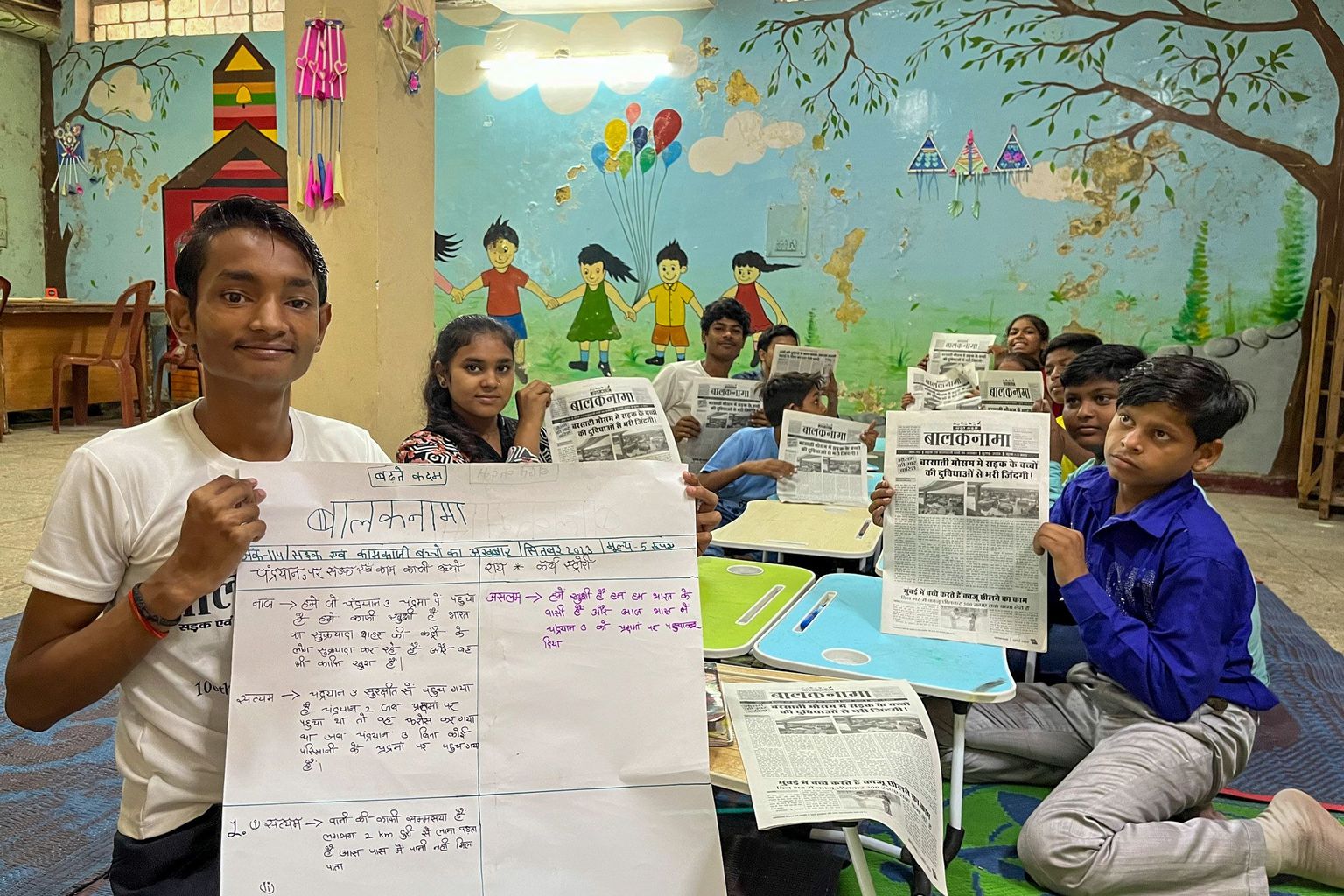

Filling the monthly tabloid is a major undertaking. Every day, nearly 100 baatooni reporters scour their neighbourhoods for leads. Good at reporting but unable to write, these so-called ‘talkative’ reporters then relay what they have uncovered to a handful of writer reporters, who pitch them to Rathore at the monthly editorial meeting. (A handful of baatooni attend these meetings as well.) If an idea sparks the team’s interest, the group gets to work verifying the details and writing up the stories. Eight thousand copies of the paper will be printed—5000 in Hindi, 3000 in English—and sold across the cities of northern India for 5 rupees (about 9 cents).

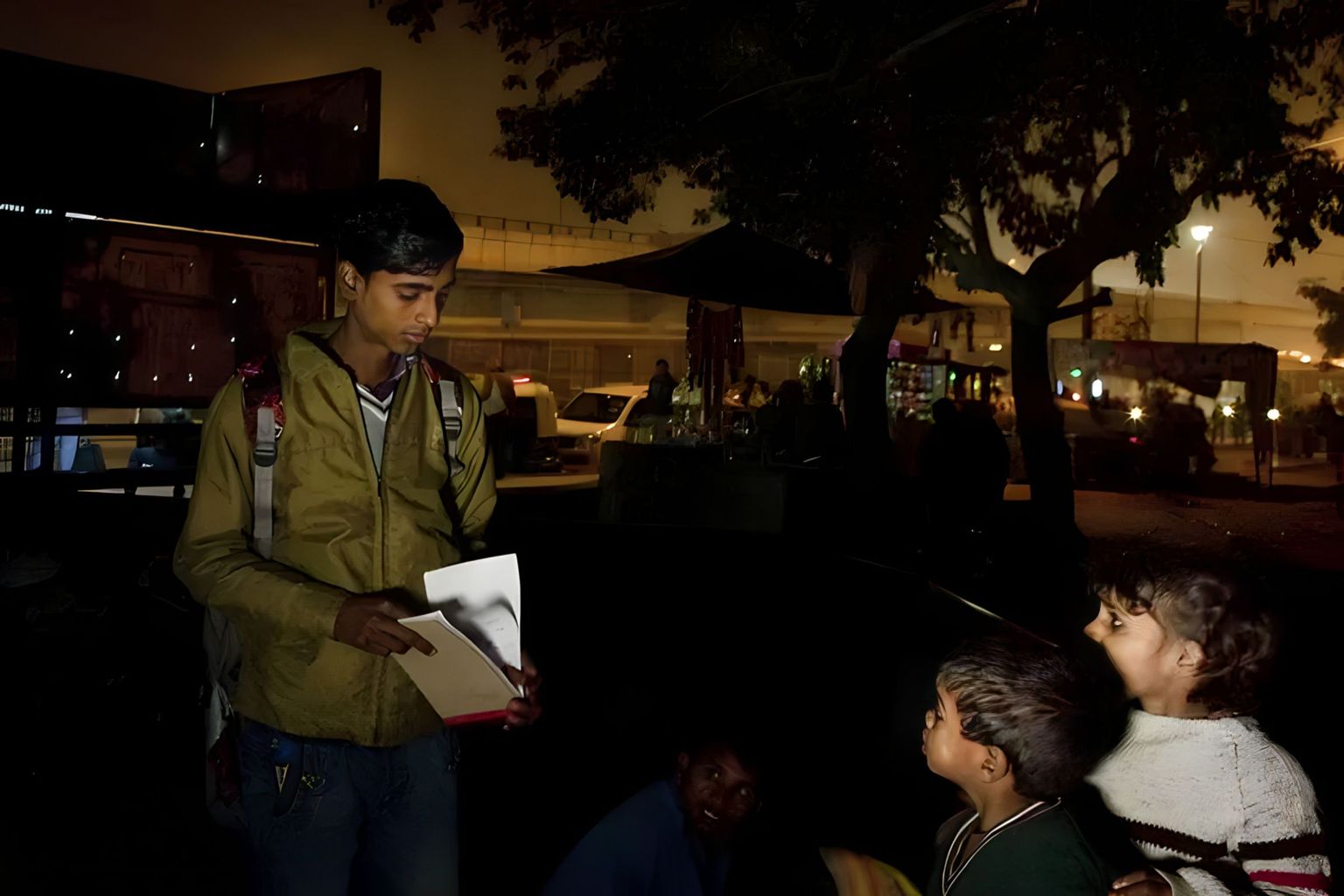

On the beat: the newspaper's editor, Kishan Rathore, speaks with children living on the streets. Photo: Mansi Thapliyal.

Writer-reporter Hansh Kumar and editor Kishan Rathor interact with street children in a makeshift tent at a slum in West Delhi. Meetings like this are a common way for Balaknama reporters to get leads. Photo: Sushmita Pathak

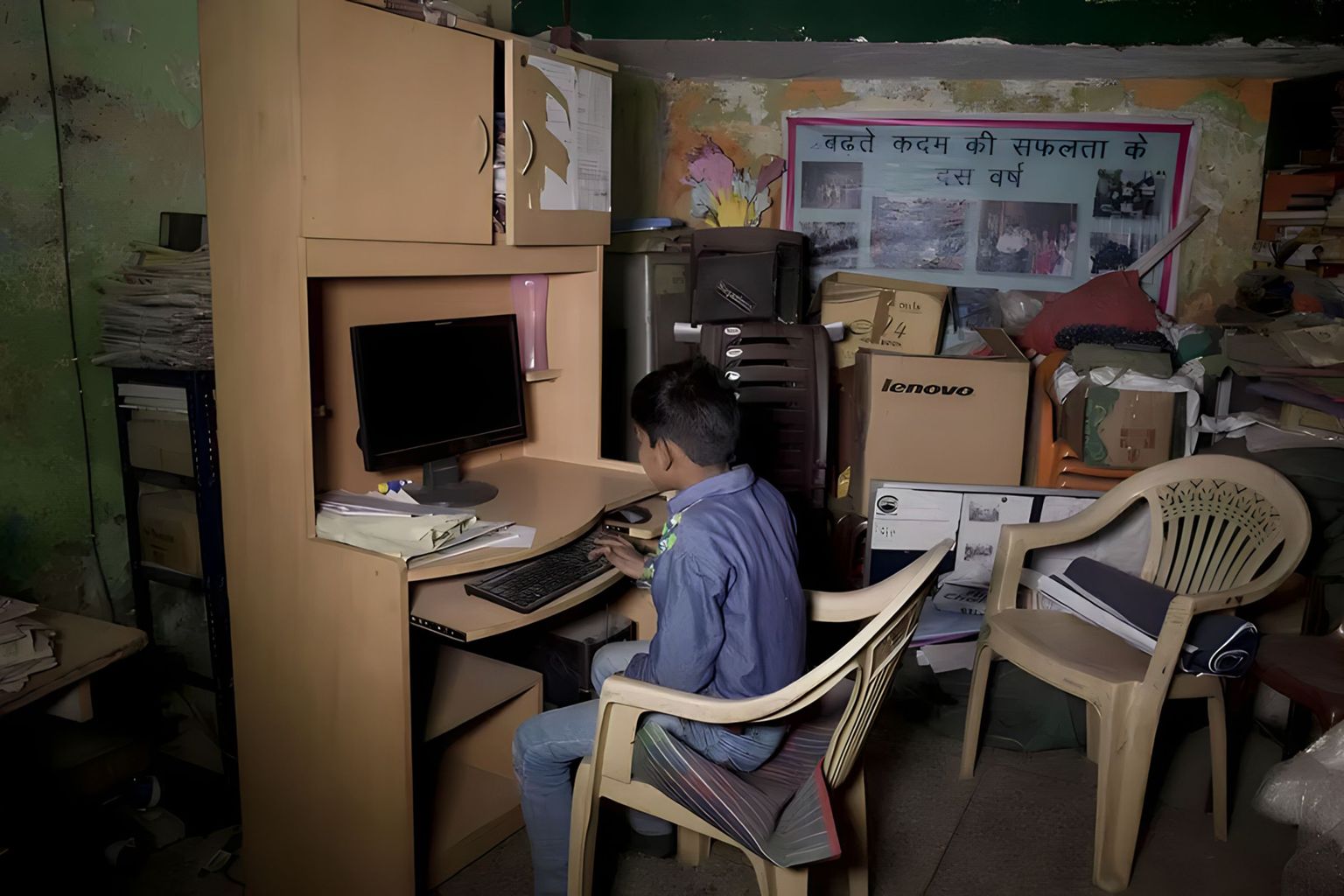

Children with typing skills are given the task of writing out the stories reported to them by so-called 'talkative' reporters. Photo: Mansi Thapliyal.

The goal, Rathore says, is to paint a picture of the challenges that India’s street children endure every day, from police harassment to dangerous child labour practices. They also highlight the small victories—the acts of bravery or generosity that work to counter the narrative of street children as nuisances or threats. In one sense, the goal is simply to shine a light on an overlooked community. As the authors of the 2021 book Lost Childhood write, “Street children are seen by all and live their lives out in the open, yet ironically very little is known about them”. Balaknama, Hindi for ‘Children’s Diary’, or ‘Voice of the Children’, is an attempt to reverse this imbalance.

But while visibility is its own objective, the paper also has loftier ambitions: speaking truth to power and affecting real change. Balaknama may not be the Washington Post, but it still manages to do this more than you might think. In 2016, the paper published an article about how the police had been using street children in Agra to clear dead bodies from railway tracks. That story eventually landed on the desk of someone high up in the government, who put a stop to the practice. Another article, about spoiled milk being served in a government-run school, was then picked up by the national papers, who magnified Balaknama’s small spotlight and pressured the authorities to fix the problem.

Hot scoops like these are every Balaknama reporter’s dream. But as with any media job, unearthing the right story takes work. Rathore says reporters often approach kids begging or selling knick-knacks at traffic stops, but that they’re often reluctant to talk. To avoid roadblocks, he instructs new recruits to attend regular meetings of street children at designated “contact points”. One such point is in the middle of a garbage dumping ground in west Delhi. About two dozen kids sit in a circle inside a tent surrounded by piles of waste as Rathore and a young reporter named Hansh Kumar, ask them questions.

The kids are shy at first, but eventually open up. One boy mentions that several of his schoolmates have missed class due to an outbreak of pink eye. Another tells the group how police chase after him when he’s picking waste up on the streets. The biggest story though is the recent death of a boy due to electrocution. “We feel scared,” the kids say. Rathore assigns this story to Kumar, who will type it out on WhatsApp on his father’s phone.

Speaking with street children is one of the most important parts of the job—though some can be reluctant to talk if trust hasn't been built. Photo: Mansi Thapliyal.

The newspaper is run from the cluttered basement of a building in Delhi. Photo: Sushmita Pathak.

Kishan Rathore and reporters storyboard ideas for the upcoming edition at the monthly editorial meeting. Photo: Sushmita Pathak.

The idea for Balaknama emerged in 2003. Sanjay Gupta, the director of a children's charity named Chetna, was meeting with a group of street children in Delhi when the conversation turned to the press. The national newspapers had recently run a story about the disappearance of a celebrity’s dog. When a child stood up and pointed out that a dog had made it into the papers but not the many street children who go missing each year, Gupta decided to make a change. He directed Chetna to fund the creation of a children-run newspaper. Balaknama was born.

In the years since, the paper has published over 100 editions. Its journalistic achievements are considerable, especially for a staff comprised mostly of illiterate or semi-literate children. But Balaknama’s impact extends well beyond the newsroom. Many of the street children who work as reporters attribute the paper to turning their lives around. Before they officially come on board, the children are enrolled in special education programs that teach them to write beginner-level Hindi. From there, Rathore and other older reporters teach the newcomers the basics of journalism, from how to type to the Five Ws to journalistic ethics, such as respecting a source’s wish not to be interviewed.

For the talkative reporters, the focus is on learning how to secure leads and identifying what it is that actually makes a story newsworthy. But Rathore and the other higher-ups also have to teach the children about right and wrong. Siraj, a scrawny 13-year-old, says that it was only by working at the paper that he learned about child labour and child marriage. “I didn’t know that these things were wrong until brother Kishan [Rathore] told me about it,” he says. Since then, he’s reported stories about both of those issues.

When children see their photo in the paper they suddenly realise that they are somebody. That’s how I felt.

While no longer a child, Rathore, now 18, says he owes a lot to Balaknama. “After my father’s death a lot of responsibilities fell on me,” he says. Rathore was just 11 years old when that happened, and he began sleeping on the streets and doing odd jobs at a liquor store to support his family. His life took a positive turn when he was introduced to Balaknama as a talkative reporter. Within three years, Rathore was running the monthly editorial meeting and mentoring new reporters. Today, he enjoys a stipend, which he uses to study, and has a room at a share house.

Rathore is not alone in singing Balaknama’s praises. Of the more than seven hundred children who have worked at the paper, many have gone on to receive bachelor’s degrees in social work before landing jobs at Chetna and other NGOs. Some even harbour dreams of making it in the media. “I want to become a television journalist at a big news channel,” Siraj says.

The effect on those the paper writes about can be just as empowering. “When children see their photo in the paper they suddenly realise that they are somebody,” says Jyoti Devi, a teenage reporter who lives with her parents under a bridge. “That’s how I felt when I first saw my picture in Balaknama. I really felt good, and after that I decided to go more often to the [Chetna-funded] learning centre.” It was there that Devi’s interest in journalism was stoked, setting her on what her mother proudly calls “a different path”.

Exposure itself will never be enough to solve the underlying issues that cause child poverty. But empowering the disenfranchised to tell their own stories, and giving them a platform to be heard, is more than a good start: it’s a direct challenge to the status quo. “I want to give people a voice,” Devi says. “Street children do all kinds of incredible things. And despite all their problems, they want to give their lives meaning. And I want to write about that.”

Rathore regularly visits slums as part of the paper's outreach with street children. This one, inside a dumping ground in West Delhi, is home to dozens of street children and their families. Photo: Sushmita Pathak.

Eight thousand copies of the paper will be printed—5000 in Hindi, 3000 in English—and sold across northern India for 5 rupees (about 9 cents). Photo: Sushmita Pathak.