What I learned about storytelling after reading every Jack Reacher novel in a year

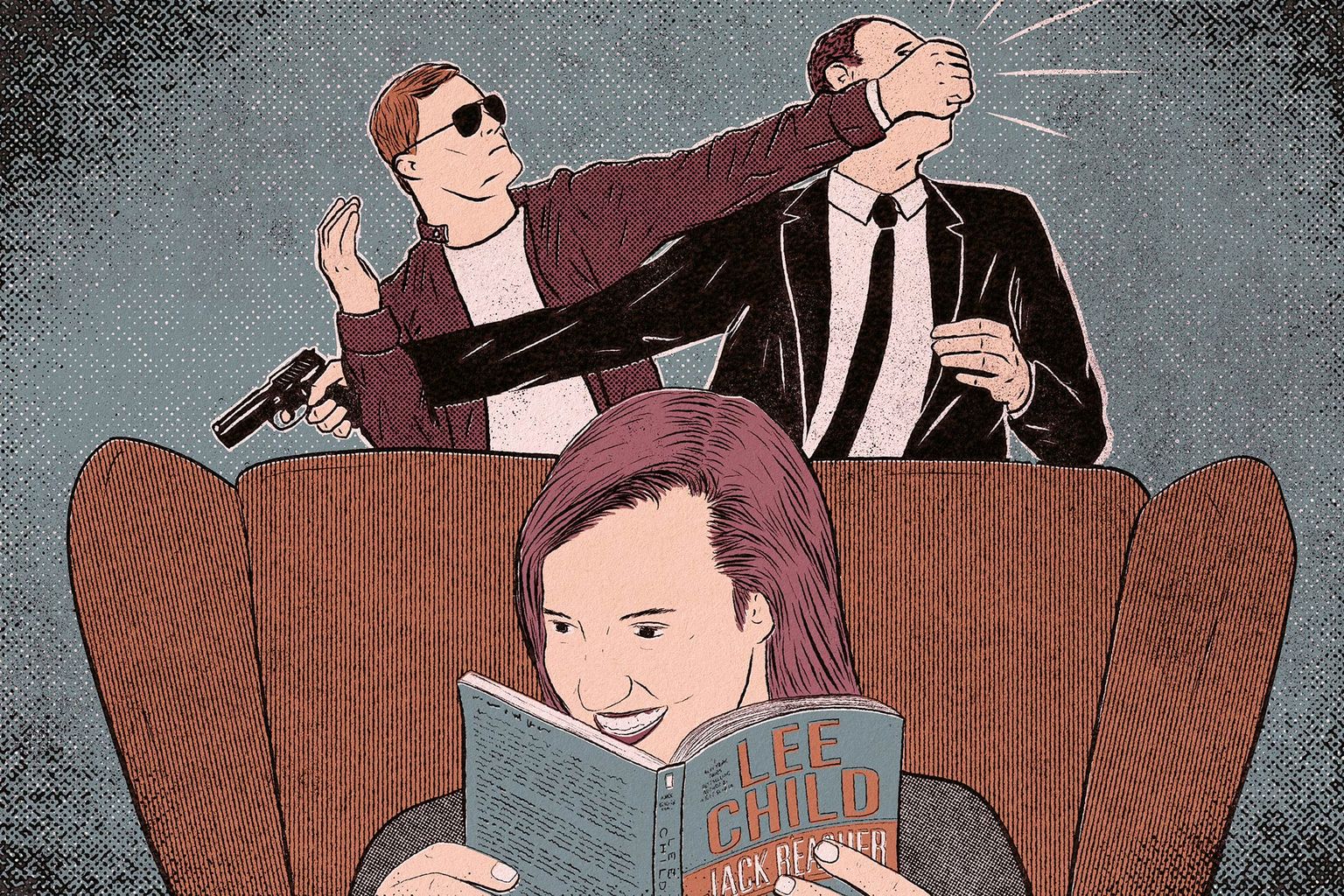

When the world shut down, writer Fleur Macdonald sought distraction in the 26 paperback books of Lee Child. She came for the punch-ups. She left with a masterclass in fiction writing.

Illustration by Jarett Sitter

Jack Reacher is better known for his perfectly calibrated headbutt than his theories on literature. But he does have them: “He liked made-up stories better, because everyone knew where they were from the get go,” the narrator explains in Make Me, the twentieth book in the Reacher series. “He wasn’t strict about genre. Either shit happened or it didn’t.”

Reacher’s creator, Lee Child, clearly subscribes to the same theory, and presumably that’s why he’s often dismissed as a minor author, someone who churns out airplane fodder, quickly read, even more quickly forgotten. One critic in The Guardian, after saying they enjoyed the stories, felt the need to add: “No one, I imagine, values Child for the quality of his prose. One can hardly find, in the entire corpus of the work, a single sentence worthy of independent admiration.”

Given these accolades, I can’t quite remember why I embarked on Reacher. I studied literature, I know I need to finish War and Peace, and I haven’t even been in an airport for a while. But last November, about three weeks into the U.K.’s sad wet second national lockdown, I downloaded the first in the series on Kindle. Perhaps the Amazon algorithm saw into my soul, or more likely I finally acted on the advice of a friend who listens to the audio versions while he illustrates children’s books, wiping the watercolour across his delicate lines as Reacher beats his enemies to a pulp. The beginning set the tone: “I was arrested in Eno’s diner.” For the next two hours, I didn’t look up.

Child famously produces one book a year, and being able to binge is one of the benefits of coming to the series over 20 years late. In the months after I first started, I read most of the series—for the plot certainly, but also for the quality of his prose. Sure, the books all follow a formula, a fact made even clearer by the Kindle’s percentage function, which allowed me to see that key plot points and literary crutches always occur at specific points. But the mastery of that formula’s execution makes Reacher a fascinating read for anyone who likes thinking about how stories work. Abstract literary principles are fine, but seeing them in action is more instructive.

And so without further preamble, here are my seven tips to effective storytelling, as gleaned from reading far too many thrillers in the midst of a global pandemic.

Rule 1: Start as you mean to carry on

The first thing to note: every Jack Reacher book starts emphatically: “The eye witness said he didn’t actually see it happen.” (Book 17). “The cop climbed out of his car exactly four minutes before he got shot.” (Book 7). “In the morning they gave Reacher a medal, and in the afternoon they sent him back to school.” (Book 21). From that opening salvo, the first chapter will then take one of two paths: it will either describe Reacher in an unexpected situation, or it will detail the gruesome death or moral agony of a minor yet crucial character. Either way, the first sentence makes you want to read the next one, and the second makes you want to read the third. It makes sense that Child says he starts a new book each September with a blank page and just one sentence; you can almost feel him being propelled by the urge to find the next perfectly distilled plot point.

Rule 2: Know your hero before the journey

From the first book, Reacher emerges fully formed, and his character development flatlines like the aftermath of a well-placed bullet. He does not have a middle name. I know this because he says so in Book 1 (at page 20). He mentions it again in Book 2 (page 86). He repeats it in Book 3 (page 374), then in Book 5 (page 410) and Book 6 (page 77). In Book 17, it’s page 159. He loves coffee (Book 1, page 53; Book 2, page 63; and Book 3, where he’s swapped his habit for three bottles of water). We may learn a few more details about his past, but there’s a satisfying sense they were always there, like scraping the foil off a pin code. That’s because Child knows exactly who Reacher is both as an individual but also as a literary figure. He’s the archetype of the American hero. A modern-day cowboy, he drifts around the States finding trouble.

Rule 3: Balance beginning, middle and end

My pandemic immersion and reading with a Kindle have made me aware of how structurally formulaic all the books are. The first chapter sets up the mystery. Then Reacher arrives on the scene. About a third of the way through the book there’s an event which makes him decide to stay. In Book 2, for example, at 28 per cent through, after a tense scene, Lee describes how Reacher shifts gears: “They had changed him from a spectator into an enemy.” At that particular moment, Reacher is chained up on a mattress in a van with a girl who may or not be a government agent. But slot it into any book in the series at around that percentage point and the sentence would probably still work. From then on, the tension builds and the mystery becomes more intricate. We are in ‘the middle’. Reacher tries to work out what’s happening; he’s always had a need to get to the bottom of things—that’s why he was such a good military police officer—and this will to know propels him, and the reader, through the narrative. The reader and Reacher stay in synch, which means Reacher functions both as hero and as audience surrogate. At 80 per cent, otherwise known as the third act or the end, he works it all out and the reader is primed, ready for an explosive resolution whose fuse has been lit from the very first chapter.

Rule 4: Think, fast and slow

Where the reader expects pace, Child holds back. “You should write the fast stuff slow and the slow stuff fast,” he’s said. The fight scenes slow down and become more balletic than brutal, carefully describing the mechanics of Reacher’s mind and the dynamics of the punch-up. What’s at stake is illusionary: whatever the plot throws at you, it’s always understood that Reacher will extricate himself alive and with more than a few dead around him (see: all the books from 1 to 27). Reacher will win, so Child shows us how. On a more structural level, pace is key. Be it a sense of foreboding, an unexpected revelation or a flash forward, each chapter end serves as a minor masterpiece in the art of the cliffhanger. Study how each functions and you’ll pick up more than in any screenwriting manual.

Rule 5: Kill your darlings, control your digressions

Reacher is economical with his words and so is Child. It is said that Raymond Chandler, known for his tersely written detective novels, was wordy till his editor got busy with his pencil. Child appears to do his own editing, killing not just most of his characters but also his darlings. It doesn’t mean the action is spare. Reacher is pedantic, a quality which often comes in use in elucidating the mystery, so any digression—on the aerodynamics of a particular bullet design or on the physics of a backswing holding a hammer—makes sense in terms of how Reacher thinks. You might be inclined to skim the works of a less-careful writer. But I enjoy every aside because I trust in Child as a storyteller. You know the road leads to the destination, but who doesn’t like a pit stop?

Rule 6: Character is king

But none of the above quite explains the appeal of series, which I attribute to the well-etched characterisations that pepper Child’s nearly ten thousand pages of action-packed prose. First of place and time. Reacher is an expert in the topography of the lost American towns at the turn of last century. But these descriptions are not just descriptive, a handy shortcut to realism. They are always in service of the plot: Reacher is either waiting in these places, running around them or blowing them up. The same goes for the characters: the baddies may be crazy, but their motives are clear and logical (at least by the internal logic permeating the Reacher universe). The cop may be old and tired and that is why he might have a heart attack. The women do not decide to hook up with Reacher because they miraculously fall for his homeless status but because he can help them, and often they end up helping him too. Women in Reacher are always strong, and he doesn’t always sleep with them.

Rule 7: Find the bigger picture

There is a before and an after in a Reacher story, just as there is a before and after in modern America. For the man brought up by a father in the army, who spent his childhood on military bases before studying at the United States Military Academy, the turning point came when he left the military. From then on he was a wanderer, living totally off-grid. That is, as he says in Book 11, until 9/11, when he was forced to get a passport and a bank account as government security tightened. For America, the turning point was also 2001, and the novels flirt with nostalgia for a time where things were less problematic: “I liked the Twin Towers. I liked the way the world used to be,” Reacher says. In the next hundred pages, quite unproblematically, he then proceeds to beat the shit out of 19 men and two trained female Afghan assassins. He then disappears from the scene, leaving no trace, ready for the next adventure.

Good fiction is about finding a bigger picture, one vaster than the nuts and bolts of prose. In The Hero, Child’s book about storytelling, Child says fiction’s purpose is “to give people what they don’t get in real life.” He’s right.

But with Reacher, it’s not about blood and guts and AWOL nuclear weapons. It’s about freedom. That’s what I felt like I was missing when I read him during lockdown. The days when I went to America and drove from San Fran to Reno in a camper van. Or stopped in a dead-end diner between New Orleans and Little Rock. I missed that feeling of not being constantly tracked by Google, Track and Trace, or border control. In one book, Reacher, who refuses to own a mobile phone, wonders at a new-fangled taxi-hailing service: “The guy from Palo Alto had a thing on his phone that summoned cars to the kerb within minutes.” The cowboys wandered America before the government. Reacher wanders an earth before data colonised us all.